Clouded Judgement 10.25.24 - Misaligned Incentives

Every week I’ll provide updates on the latest trends in cloud software companies. Follow along to stay up to date!

Misaligned Incentives

In the venture capital world, there are largely 3 constituents: The GPs (investors), the LPs (pension funds, endowments, universities, family offices, sovereign wealth funds, etc who give money to GPs), and founders (portfolio companies). In the early days of venture capital, it felt like the incentives were all quite aligned between these 3 groups. Win together, lose together. There were even specific mechanisms introduced in the GP - LP part of the equation to ensure this - the GP commit. This is the amount of money the partners themselves commit to the fund, oftentimes expressed as a percentage of the overall fund size. As a GP, if your own money was at stake, you’d put more thought into every individual investment.

Today, I want to talk about the GP - Founder leg of the equation, and how the incentives are diverging. I think it’s an important dynamic for all founders to recognize. In order to have this conversation, we must first start with defining the incentives. For the GP, the monetary incentives are two fold - salary and carry. Or, “2 and 20.” Venture funds charge a management fee based that is a percentage of the fund size, collected annually. Generally this is ~2%. Then there is carry, or the GP’s share of profits. Generally, this is ~20%. To make it concrete - let’s use an example of a $100m fund that gets to a 3x. In this scenario the GP will collect ~$2m annually (used to pay fund operating expenses and salaries of the team), and $40m of carry ($100m fund turns into $300m, which translates to $200m of profits, and 20% of that is $40m). There’s nuance here, but broadly the 2% lasts for ~10 years, and steps down over time (probably averages closer to ~1.5% annually blended over 10 years).

For founders - the monetary incentives are clear. Build a large business where the equity stake translates into significant value!

There are of course non-monetary incentives, but for now just focusing on the monetary ones. If we rewind the clock 15-20 years, fund sizes were significantly smaller. The 2% (annual management fees) part of the equation was nice, but if you wanted to “get rich” it was all about maximizing the 20%. In this path, the GPs and Founders win together - with large company exits. It was the singular focus of GPs and founders. With LPs benefiting as well!

Today - the equation is changing. Fund sizes have ballooned significantly. There are different pools of LP capital available with a lower cost of capital (ie lower return expectations). So much so, that the 2% part of the equation is very meaningful given the size of funds! In the past, to “get rich” as in investor it was all about maximizing the 20%. Today, with fund sizes where they are, many are instead looking to optimize for the 2%. This means raising as much as possible, and deploying as much as possible (as quickly as possible). Remember, the management fee is “guaranteed.” The 20% (the carried interest) is variable. It’s economically rational to look to optimize and maximize the guaranteed portion…

It’s important to call this out because this is where the incentives start to diverge between GPs and Founders. In the past, the only path to “get rich” for GPs ALSO resulted in a “get rich” path for founders. Today there is a “get rich” path for GPs where the outcome of the founders is irrelevant. Doesn’t matter how the underlying companies in a fund perform, you collect the annual management fees regardless.

So what does this mean for founders? First off - venture capitalists are playing a different game today. When optimizing for dollars raised and dollars deployed it becomes much more of a deployment game for venture capitalists. How can you deploy a high volume of dollars in a shorter window of time so you can raise the next fund and add to the AUM base of the firm (and thus aggregate more management fees). This shows up in a couple ways that is relevant to founders:

All too often I see companies raising too much money too early on. Why? Well, one reason is what I’ve laid out above. Firms want (need) to invest larger and larger sums of money to deploy their larger and larger funds. As a founder, you may go out looking to raise a $50m round, and before you know it you’re getting offers for a $100m+ round. On the surface, this may appear great! What’s so bad about doubling the cash on your balance sheet? Well, it often comes with a much higher valuation. But again, why is this bad?? I’ve written about this before, but over capitalizing and over valuing your business too early on can become a real risk…I hope we all learned that lesson from the 2020-2022 period. So for founders - the important question to ask is “am I being offered more money at a higher valuation because the investor truly believes more than anyone else, or are they just playing a deployment game? Are they trying to put together an offer that maximizes the chance of success for my company, or are they putting together an offer that is ideal for their fund?” I promise you, a lot of the rounds from the 2020-2022 period where founders thought “highest valuation term sheet = highest conviction” turned out to be anything but…

Call Options. Venture today has turned into a game of buying deep out of the money call options… Take a swing, hope it works, and if it doesn’t move on to the next swing. Power law outcomes will make it all work... The unfortunate part is the GP / Founder relationship becomes a lot more transactional as a result of this mentality. If your job as an investor is to always go find the next investment to deploy the next dollar, it gets really hard to actually slow down and work with each portfolio company / board you're on. The mentality instead becomes “invest the dollars, then let the companies play out.” It becomes a lot harder to “justify” spending time with companies that are struggling or ones that get stuck. And on top of this, to my point above, if your investors didn’t have the deep conviction at the point of investment, they’re a lot more likely to abandon ship and give up on the founders too early at the first sign of a challenge (or in other cases, become adversarial). I don’t want to imply VCs are savants who can turn around struggling companies, but I do believe that having board members and investors who are there for you in the tough times matters. Reality is founders “need” their inventors less when times are good…

Number of boards / investments. This one is a bit more obvious, but with a fund optimized for size / deployment cadence, the reality is every individual investor will end up with A LOT of investments of their own. And each individual can only spread themselves so thin… As founders you should definitely ask how many other companies the investors work with? If the answer is 30+, how much time do you think they’ll realistically be able to allocate to you?

In summary - the venture ecosystem has evolved significantly in the last 5 years. For founders - ask yourself this question when deciding on who to work with. “Am I working with a 2% or a 20% venture firm?” The 2% firms are optimizing for deployment. The 20% are optimizing for large company outcomes. There’s one path where the incentives are aligned. I’m not meaning to imply big funds = bad. But there is a culture and mindset that starts to creep in the larger and larger funds get, and it’s up to founders to determine which investor falls into which bucket.

Quarterly Reports Summary

Top 10 EV / NTM Revenue Multiples

Top 10 Weekly Share Price Movement

Update on Multiples

SaaS businesses are generally valued on a multiple of their revenue - in most cases the projected revenue for the next 12 months. Revenue multiples are a shorthand valuation framework. Given most software companies are not profitable, or not generating meaningful FCF, it’s the only metric to compare the entire industry against. Even a DCF is riddled with long term assumptions. The promise of SaaS is that growth in the early years leads to profits in the mature years. Multiples shown below are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value (market cap + debt - cash) / NTM revenue.

Overall Stats:

Overall Median: 5.6x

Top 5 Median: 16.7x

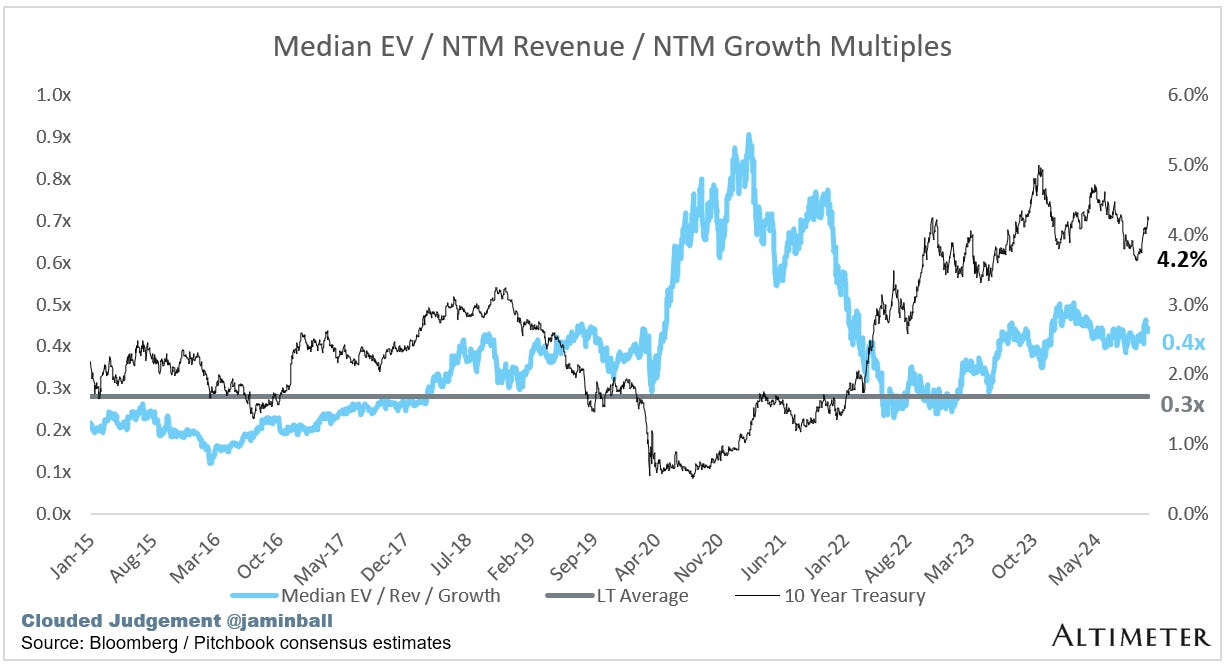

10Y: 4.2%

Bucketed by Growth. In the buckets below I consider high growth >27% projected NTM growth (I had to update this, as there’s only 1 company projected to grow >30% after this quarter’s earnings), mid growth 15%-27% and low growth <15%

High Growth Median: 10.8x

Mid Growth Median: 9.4x

Low Growth Median: 4.1x

EV / NTM Rev / NTM Growth

The below chart shows the EV / NTM revenue multiple divided by NTM consensus growth expectations. So a company trading at 20x NTM revenue that is projected to grow 100% would be trading at 0.2x. The goal of this graph is to show how relatively cheap / expensive each stock is relative to their growth expectations

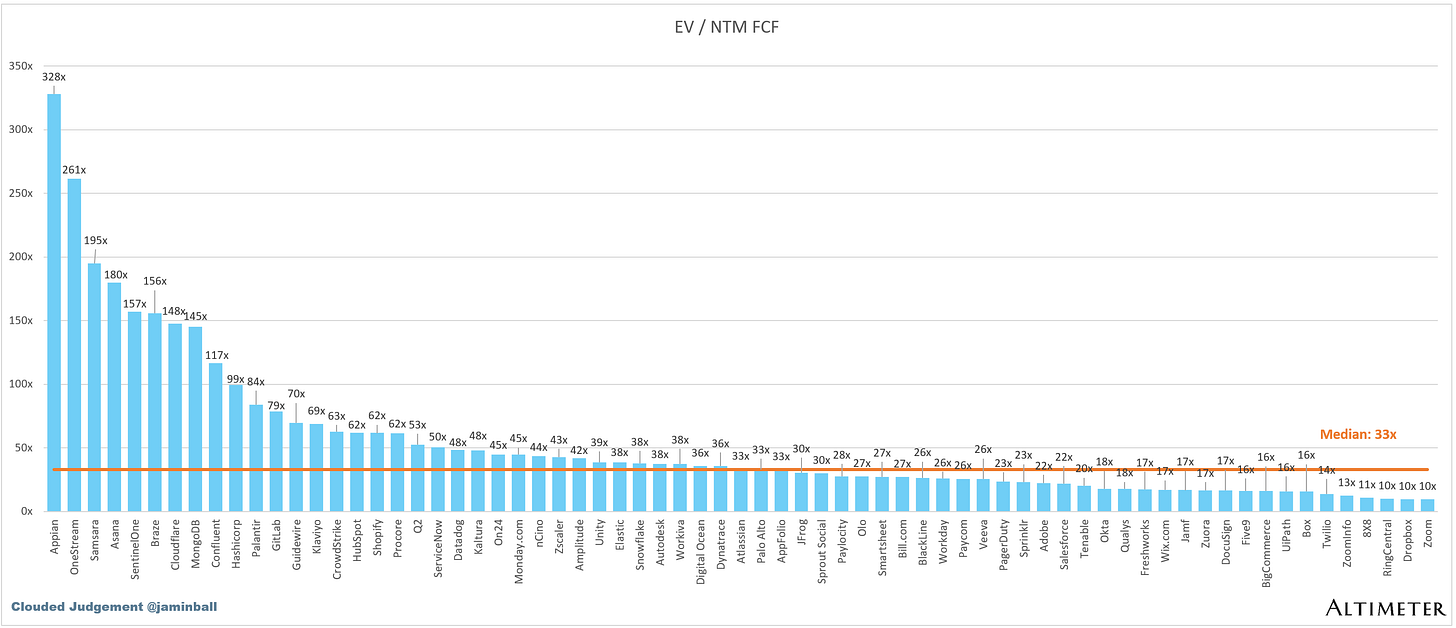

EV / NTM FCF

The line chart shows the median of all companies with a FCF multiple >0x and <100x. I created this subset to show companies where FCF is a relevant valuation metric.

Companies with negative NTM FCF are not listed on the chart

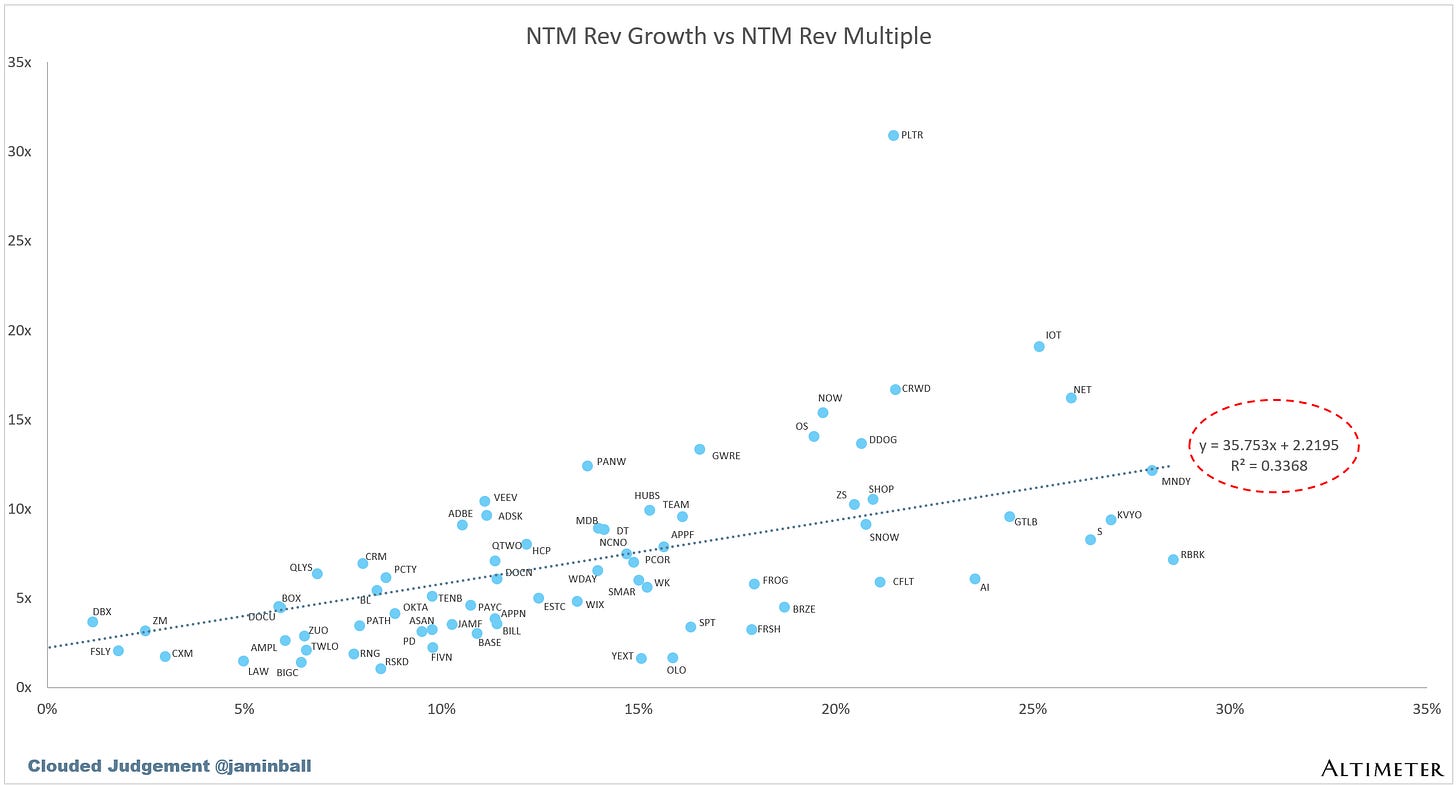

Scatter Plot of EV / NTM Rev Multiple vs NTM Rev Growth

How correlated is growth to valuation multiple?

Operating Metrics

Median NTM growth rate: 11%

Median LTM growth rate: 16%

Median Gross Margin: 75%

Median Operating Margin (9%)

Median FCF Margin: 15%

Median Net Retention: 110%

Median CAC Payback: 39 months

Median S&M % Revenue: 41%

Median R&D % Revenue: 25%

Median G&A % Revenue: 17%

Comps Output

Rule of 40 shows rev growth + FCF margin (both LTM and NTM for growth + margins). FCF calculated as Cash Flow from Operations - Capital Expenditures

GM Adjusted Payback is calculated as: (Previous Q S&M) / (Net New ARR in Q x Gross Margin) x 12 . It shows the number of months it takes for a SaaS business to payback their fully burdened CAC on a gross profit basis. Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, so I’m taking an implied ARR metric (quarterly subscription revenue x 4). Net new ARR is simply the ARR of the current quarter, minus the ARR of the previous quarter. Companies that do not disclose subscription rev have been left out of the analysis and are listed as NA.

Sources used in this post include Bloomberg, Pitchbook and company filings

The information presented in this newsletter is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect the view of any other person or entity, including Altimeter Capital Management, LP ("Altimeter"). The information provided is believed to be from reliable sources but no liability is accepted for any inaccuracies. This is for information purposes and should not be construed as an investment recommendation. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. Altimeter is an investment adviser registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not constitute an offer to sell, or a recommendation to purchase, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security, nor a recommendation for any investment product or service. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, neither the author nor any of his employers or their affiliates have independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author and all employers and their affiliated persons assume no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

I think this topic is pretty misunderstood. I saw this analysis from a family office on early stage VC returns over the last 25 years where the median IRR was 7% and mean was 50% - power law distribution. What this says is that if you were able to index all of VC you would capture the mean. The problem is indexing the mean is not simple. The outliers and when I mean outliers I am talking the decacorns are so rare. And because they are so rare, their view was that you would need to capture at least 20% of all the underlying early stage VC deals in order to have high certainty you capture the mean. I call this the good lottery odds problem. If the jackpot was $1 billion and your odds were 1 in 100 million BUT you only had $100k of life savings, would you buy $100k of lottery tickets? The odds are great if you have a ton of scale. The problem with VC is the volatility because of the lower percentage of huge outliers. So in this argument, maybe this why capital is flowing for funds to be bigger. The more bets you make in a fund especially if your ability to pick and more importantly win the best deals is higher may allow you to more CONSISTENTLY capture the outliers thus reducing volatility and getting the mean IRR. Ultimately I think Tiger was trying to do this strategy but did it at the absolutely peak of the market. If their funds weren't one year funds but multiple years, they would have Vintage diversity and their strategy may have worked......yep, hot take.

Great commentary on the change of incentive alignment towards 2% GP fee optimization.