Every week I’ll provide updates on the latest trends in cloud software companies. Follow along to stay up to date!

Let’s Talk About SBC

I need to put on all my body armor before jumping into a topic as controversial as SBC (stock based compensation)… It’s a bit of a longer post so bear with me. First let’s define it for those who aren’t familiar with SBC. At most (all?) cloud software businesses compensation comes in two parts. Salary (cash) and equity grants (SBC). SBC is generally expressed as a dollar value (eg “we’re granting you $400k worth of equity over 4 years), it vests (typically a 1 year cliff and then quarterly), and can be granted as options (there’s an exercise price) or as RSUs (no exercise price). It also generally represents a large portion of total comp! The exercise price represents the price at which employees can purchase shares. If the exercise price is $80 and the stock is trading at $100 employees can exercise (buy for $80) and then sell for $100 on the open market for a $20 / share profit. At the time of this exercise, 1 additional share enters into the public markets (dilution).

Current software valuations (multiples) today have put an extra emphasis on profitability (FCF). The biggest question around SBC today is - Should SBC be subtracted from FCF? Because SBC is a non-cash expense it is added back to FCF (under standard FCF calculations). This means companies take their net income (or more commonly net loss) and add back SBC (among other adjustments like D&A, working capital, etc). The reason SBC is so controversial is most (~60%) of public cloud software companies have positive FCF, but a huge percentage of that FCF is sitting in SBC. Said another way, software companies do not generally have any FCF if you subtract SBC. Wrapping up the key question - if we’re now using FCF multiples (not revenue) to value software businesses, should the FCF being used in the FCF multiple be the standard value of FCF or the value with SBC subtracted? Because SBC represents a large % of FCF (oftentimes >100% of FCF) there are huge valuation implications of this question. Many will look at SBC as an expense, and therefore argue it should be expensed as one (eg a cash expense). The tricky part is that it’s not a cash expense.

The other reason SBC is such a tricky topic is that it’s not clear what the actual $ expense should be (if you view it as a cash expense). One thing I have a strong point of view on - the dollar value of SBC on the cash flow statement is most definitely NOT the right value to use for SBC if you want to subtract it from FCF. Why? As I understand it the dollar value of SBC on the cash flow statement represents the dollar value of an option package based on the share price at the time of the options being earned (vested). It’s actually more complicated than this, and weighted average prices are used, but I’m simplifying it for the example. If an employee owned options at a $80 strike price, and those options vested when the share price was $100, the dollar value of SBC on the FCF statement is equal to $20 (share price - strike price) x # options. This is irrespective of whether the options are exercised, and is locked in (it doesn’t change as share price changes). What does this mean? In an environment of a stable share price the dollar value of SBC on the cash flow statement is probably about right. However, in a period of a rapidly declining share price the dollar value of SBC on the cash flow statement grossly overstates the actual dollar value of SBC. Let’s use the example above again. When the share price was $100 when options vested there was a SBC dollar value locked in. Now let’s say that companies share price declines 50% (most software companies have). Now the share price is $50 and those options are worth ZERO to the employee (you would never exercise an option to buy at $80 when you could buy in public markets for $50). However, there is still a SBC value on the cash flow statement. At the same time and for the same logic, in a period of a rapidly appreciating share price the dollar value of SBC on the cash flow statement grossly understates the true value of SBC.

The true cost of SBC lies in the inherent dilution it causes. When options are granted and then exercised the share count of a company goes up. For the cloud software universe on average share counts increase by anywhere from 1-5% per year, and this increase is driven by equity compensation, or SBC. Why is this an issue? Let’s say the value of a company stayed constant. If the share count goes up, the share price goes down (even though the overall business is still worth the same amount). Share price is just market cap / # shares. So if the numerator stays constant and the denominator increases the output goes down. This means that while companies grow their overall business (and thus the value of their business), the increase in share count is a headwind to share price even while the overall business is worth more. Hopefully I’m not loosing people yet…

So what’s my take on SBC? I don’t think we should subtract it from FCF, but should instead model in future dilution as we’re calculating future returns (and therefore what multiple / price we’re willing to pay today for “fair value”). And here’s the most important part - since dilution does act as a headwind to returns and present value share price, companies that dilute themselves “above average” from SBC should receive a lower multiple, all else being equal. I’m going to steal an AMAZING framework that Keith Weiss from Morgan Stanley laid out in a note he wrote on SBC from a few weeks ago. The following paragraph paraphrases his work with some of my own thoughts mixed in. In general, we use revenue multiples to asses relative valuations of software companies. I get darts thrown at me all the time on twitter for using revenue multiples, but here’s why - what other metric would you use to asses relative valuation of an entire industry? Not all have positive FCF, and almost none have positive net income for a PE multiple. Therefore we have to use revenue multiples. It’s an inexact science, or as Keith calls it a “necessary evil.” Here’s how revenue multiples have evolved. First, we saw variance in revenue multiples based on revenue growth rate. A business growing faster than a comparable business should get a higher multiple. Call this a growth-adjusted revenue multiple. Then, we looked at also adjusting for profitability (FCF margin or Operating margin). Let’s use two companies as an example. To further simplify the hypothetical let’s say both companies operate in the exact same market. Company A is growing 50% YoY with 25% FCF margins. Company B is growing 50% YoY with 0% FCF margins. If we just growth adjusted these two businesses they’d have the same multiple. Obviously company is A is more attractive, so we’d give them a premium revenue multiple to company B. Where we’ve gotten to as an industry (and in this example) is profitability-adjusting growth adjusted revenue multiples (it’s a mouthful, but just wait…). What we’re saying now with SBC is that there’s a THIRD factor we need to adjust revenue multiples by - dilution! Let’s do another hypothetical. Company A is growing 50% YoY with 25% FCF margins and 1% annual dilution from SBC. Company B is growing 50% YoY with 25% FCF margins and 5% annual dilution from SBC. Just looking at the profitability-adjusted growth-adjusted multiple they’d trade at the same multiple. But company A will see far less future dilution so we should be willing to pay more for it today! Therefore, company A should have a higher revenue multiple when we dilution-adjust the profitability-adjusted growth-adjusted revenue multiple (now we really have the tongue twister).

Where we’ve gotten is a revenue multiple that ends up being influenced by many other factors outside of the simple dollar revenue value (growth, profitability and dilution). There are obviously other factors backed in to a multiple that will give businesses premiums / discounts (TAM considerations, strength of management teams, etc). So while a revenue multiple does seem simplistic, there are way more factors backed in. Clearly over the last 18 months every factor outside of growth has been thrown out the window which was a terrible assumption to make. Only growth mattered! Now profitability and dilution matters. The important statement being they’ve always mattered, but the public markets are now putting the appropriate weight on them. Net net my take is that SBC does not need to be subtracted from FCF, but should be factored into the fair value multiple (either revenue or FCF multiple)

So how much should we discount revenue multiples for companies who are guilty of over-diluting shareholders? The framework Keith came up with was:

“Bottom-line from our analysis, for every additional percentage point of share dilution seen from SBC versus the industry average – 2.5% per year for 15-30% growers and 4% per year for 30%+ growers, we estimate EV/Sales multiples should be adjusted down by ~6%.”

I think this is a very helpful framework. Keith later shared a chart of high growth software businesses and estimated how much their current revenue multiple either overvalued or undervalued the true value of each business based on growth, profitability (operating margin) and SBC (dilution). The chart is a bit tricky to read, but the black dots for each name are the takeaway. A negative value implies the revenue multiple today is too high (eg HashiCorp’s revenue multiple should be 83% lower when factoring in growth, profitability and SBC). Conversely, a company like Smartsheet should have a revenue multiple 92% higher given its growth, profitability and dilution.

This is all an inexact science, but a helpful framework

A post for another time is the hidden cost of SBC. When stocks decline, the equity component of employees comp goes down dramatically. Employees who thought they were making $XX/ year, are now making $0.5X / year given their equity is either underwater (options out of the money) or worth a lot less (RSUs). The big question management teams will face is what do they need to do to retain employees? Do they need to issue more shares to “make them whole?” Or lower the exercise price of options for those that are underwater? Either option adds a lot more dilution to shareholders (and as laid out in the analysis above should result in a hit to revenue multiples). If companies had to offer X shares to give out $100k / year in equity, they now have to offer 2x, which comes with incremental dilution. SBC can be a negative downward spiral if management teams aren’t careful when stock prices declines. It’s important to do what necessary to retain employees in a way that doesn’t disrupt the business. Equity should be thought of as variable comp where you as an employee get to share in the upside (and downside) of company growth, but over the last ~5 years it’s shifted where employees think of it as guaranteed comp, not variable comp.

Top 10 EV / NTM Revenue Multiples

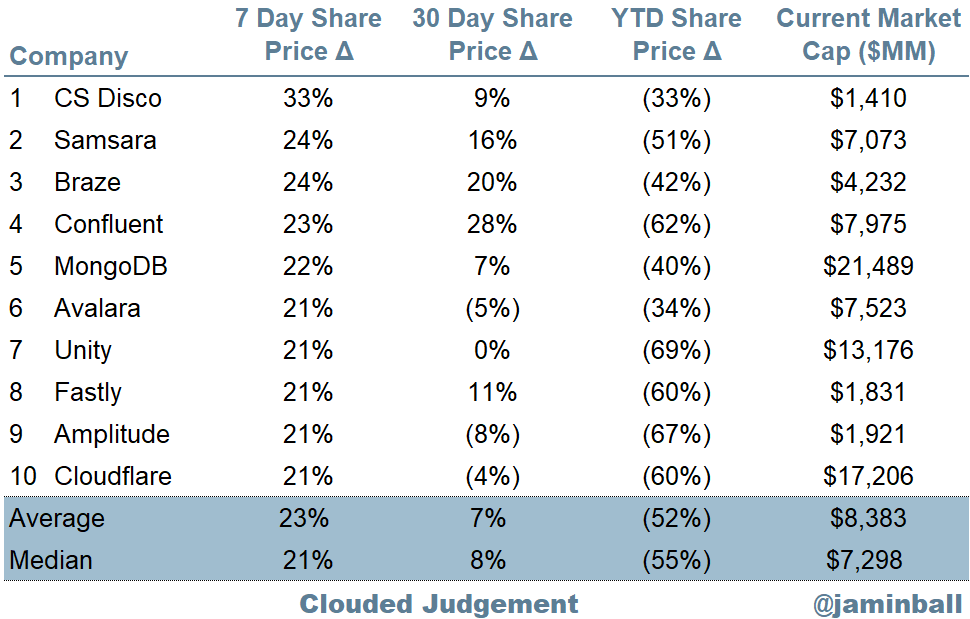

Top 10 Weekly Share Price Movement

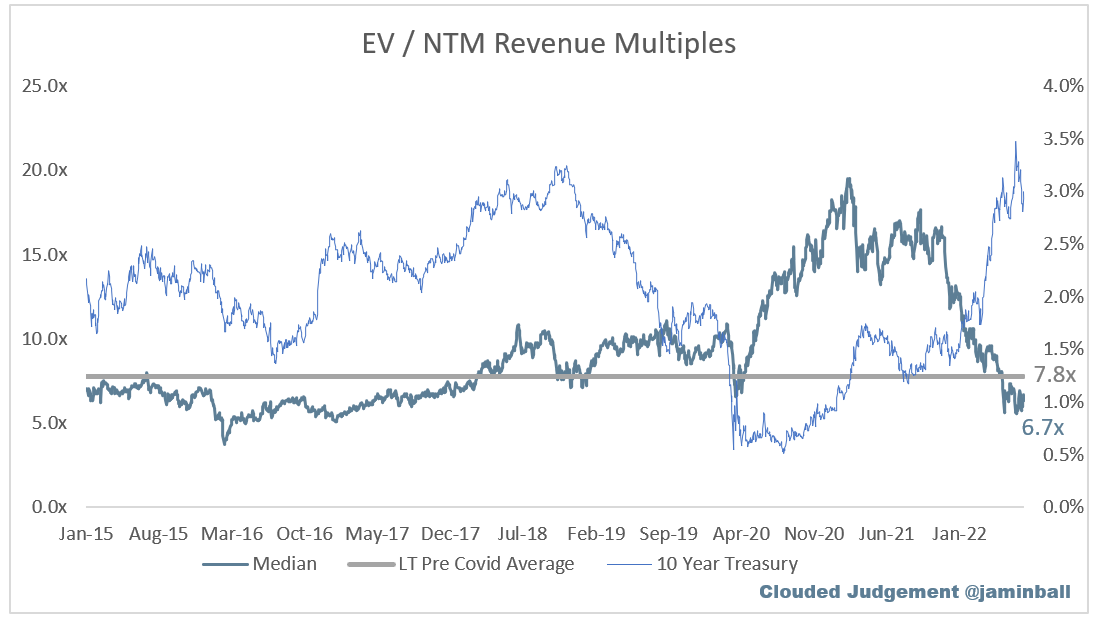

Update on Multiples

SaaS businesses are valued on a multiple of their revenue - in most cases the projected revenue for the next 12 months. Multiples shown below are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value (market cap + debt - cash) / NTM revenue.

Overall Stats:

Overall Median: 6.7x

Top 5 Median: 17.9x

10Y: 3.0%

Bucketed by Growth. In the buckets below I consider high growth >30% projected NTM growth, mid growth 15%-30% and low growth <15%

High Growth Median: 9.4x

Mid Growth Median: 7.0x

Low Growth Median: 4.0x

Scatter Plot of EV / NTM Rev Multiple vs NTM Rev Growth

How correlated is growth to valuation multiple?

Growth Adjusted EV / NTM Rev

The below chart shows the EV / NTM revenue multiple divided by NTM consensus growth expectations. The goal of this graph is to show how relatively cheap / expensive each stock is relative to their growth expectations

Operating Metrics

Median NTM growth rate: 24%

Median LTM growth rate: 32%

Median Gross Margin: 74%

Median Operating Margin (25%)

Median FCF Margin: 3%

Median Net Retention: 120%

Median CAC Payback: 34 months

Median S&M % Revenue: 46%

Median R&D % Revenue: 27%

Median G&A % Revenue: 20%

Comps Output

Rule of 40 shows LTM growth rate + LTM FCF Margin. FCF calculated as Cash Flow from Operations - Capital Expenditures

GM Adjusted Payback is calculated as: (Previous Q S&M) / (Net New ARR in Q x Gross Margin) x 12 . It shows the number of months it takes for a SaaS business to payback their fully burdened CAC on a gross profit basis. Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, so I’m taking an implied ARR metric (quarterly subscription revenue x 4). Net new ARR is simply the ARR of the current quarter, minus the ARR of the previous quarter. Companies that do not disclose subscription rev have been left out of the analysis and are listed as NA.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not constitute an offer to sell, or a recommendation to purchase, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security, nor a recommendation for any investment product or service. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, neither the author nor any of his employers or their affiliates have independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author and all employers and their affiliated persons assume no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

"So what’s my take on SBC? I don’t think we should subtract it from SBC" I think you mean FCF in the second sentence.

Thanks for the great write up. Can you share a link to Keith’s report?