A Look Back at Q4 '20 Public Cloud Earnings

Q4 earnings season for cloud businesses is now behind us. The 60 companies that I’ll discuss here (which is not an exhaustive list, but is still comprehensive) all reported quarterly earnings sometime between January 27 – March 31. For this recap I’ve added Qualtrics to the analysis (in addition to the names from the Q3 analysis). In this post, I’ll take a data-driven approach in evaluating the overall group’s performance, and highlight individual standouts along the way. As a venture capitalist, I naturally cater my analysis through the lens of a private investor. Over my ~5 years as a VC, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with hundreds of entrepreneurs who are all building special companies. Through these interactions, I’ve built up mental benchmarks for metrics on which I place extra emphasis. My hope is that this analysis can provide startup entrepreneurs with a framework for how to manage their businesses around SaaS metrics (e.g., net retention and CAC payback). Let’s dive in.

Update on Public SaaS Valuations

Before getting into the Q4 data, it’s important to frame the conversation around valuations. Just about all cloud companies are valued off a multiple of their revenue. That is, their Enterprise Value / NTM (Next Twelve Months) Revenue. We use forward revenue estimates as a company’s future outlook determines its worth. As you’ll see from some of the charts below, revenue multiples across the board are sitting at all time highs. The chart below shows the median, as well as 3 month and 1 year rolling average for the entire cloud universe.

Double-clicking one layer further, we can separate the median multiples into different growth buckets. In the below chart I define High Growth as >30% projected NTM growth, Mid Growth as 15%-30% and Low Growth as anything <15%.

As you can see, multiple contraction within the Cloud universe has been quite sharp recently. Multiples peaked in early Feb, and since then we have seen the overall median Cloud multiple compress ~24% (20x to 15x). The multiple compression for high growth businesses has been the most severe, compressing ~40% from highs (42x to 25x). However, looking at these charts it’s easy to pick up that even with this recent drop in multiples, we’re still sitting well above the pre-Covid highs. Overall, median cloud multiples are still 33% higher than were they were immediately before Covid.

So what does this imply? Are we only halfway through the drop to a “new normal” with more pain ahead? Or are we set for a rebound? It’s all very hard to answer. My personal take – given the drastic increase in the money supply, and an overall greater appreciation for the strength of cloud business models, I do think the median cloud multiple will restate a bit higher than where they were pre-Covid. That doesn’t mean we’ll never drop to levels below pre-Covid multiples, however I do think the equilibrium state is above where multiples were pre-Covid. How much higher, and am I correct in this assumption? Only time will tell.

What Caused the Sudden drop in Multiples?

For a long time we’ve known cloud multiples were unsustainable. I grabbed the below screenshot from my quarterly Q3 cloud earnings recap where I talked about this:

But what then caused the sudden drop? For the most part the fed has stayed consistent in their messaging of rates staying low, fiscal stimulus has only injected trillions more into the economy (with more potentially on the way), and digital transformations are still accelerating. So what gives? Many people turn to the 10 Year Treasury rate as an explanation. A quick history - Zooming out back to 2008, the 10 Year rate dropped from ~4% to ~2% over the span of ~4 years to 2012. Since then, it has oscillated predominantly in the 2-3% range. When Covid hit, we saw the rate drop precipitously down to ~0.6%. However, since Fall ’20 the 10 Year has steadily risen (as have multiples before their drop in early Feb). The current 10 Year rate is ~1.7%.

If we look back over an extended period of time there really is very little correlation between the 10 Year rate and cloud multiples. For the most part, they move and swing independently of one another. However, there are a few periods of extreme correlation, and we’re in one of those periods currently. Below you can see a graph of the 10 Year rate (right axis) and median cloud multiples (left axis) from the time multiples peaked in early Feb until now. From that point in time the correlation between the two is -0.95. This level of correlation is EXTREME. I don’t think I’ve ever run a correlation that yielded a result this high.

A very plausible claim is that multiples were due for a correction, and this correction just happened to take place in a period of the rising 10 Year, and therefore the correlation is “random.” The below tweet encapsulates this:

Is it a random coincidence, or is something more going on? The correlation has only been strong for ~2 months which isn’t the longest sample set. My take – the correlation is not random at all. What I believe happened is the 10 Year rate started to show strength above certain levels (>1%), and once this happened multiples began to drop as large quantities of money flowed out of equities (thus dropping multiples). The 10 Year rate only broke 1% in early January. Over the next month it oscillated up and down between 1-1.1% but never really showed evidence of a longer run up. However, from 1/27 to 2/5 we saw a steady increase from 1.02% to 1.17%. Over the next month we’ve seen the 10 Year rise to ~1.7%. I believe that once the 10 Year rate showed strength >1% (what we saw in the rise from 1/27 – 2/5), it gave a big population the confidence that bond and credit markets were strengthening, and large quantities of money flowed out of equities and into these markets. At the end of the day, large money flows trump all else.

What happens over the next quarter will be extremely interesting, and I can’t wait to follow along. But for now, let’s dig in to the Q4 results for Cloud companies.

Q4 Big Winners

If you don’t have time to read the rest of this article, here are the companies who I believe really stood out (from a financial perspective). They represent my “Q4 Big Winners.” The 3 companies in the box are the elite performers.

Q2 Revenue Relative to Consensus Estimates

Now let’s dive in to the financial results of Q4 starting with revenue. Beating consensus revenue estimates is the first aspect of a successful quarter. So what are these consensus estimates and who creates them? Every public company has a number of equity research analysts covering them who build their own forecasted models, which combine guidance from the company and their own research / sentiment analysis. The consensus estimates are the average of all the individual analysts’ projections. Generally when you hear “consensus estimates” it refers to revenue and earnings (EPS), but for the purpose of this analysis we’ll just be looking at revenue consensus estimates (as this is the metric these companies are valued off). For every public company the expectation is that they’ll beat consensus estimates, because companies often guide research analysts to the lower end of their internal projections. They do this to set themselves up to consistently beat estimates, demonstrating momentum. Cisco, for example, famously beat earnings expectations for 43 straight quarters in the 1990s.

It’s also important to note that when a company is providing guidance for the “next quarter,” it is (in some cases) already halfway through that quarter due to the timing of earnings calls. By then, the company generally has a good sense for how the quarter is going and can guide ever so slightly under their internal projections. As the data shows below, the median “beat” of quarterly consensus estimates was 5.3% in Q4 (it was 4.6% in Q3, 4.1% in Q2, and 3.9% in Q1). It is interesting that the median beat of quarterly consensus estimates have been going up each quarter.

As you can see from the data below the vast majority of cloud businesses beat the consensus estimates for Q4.

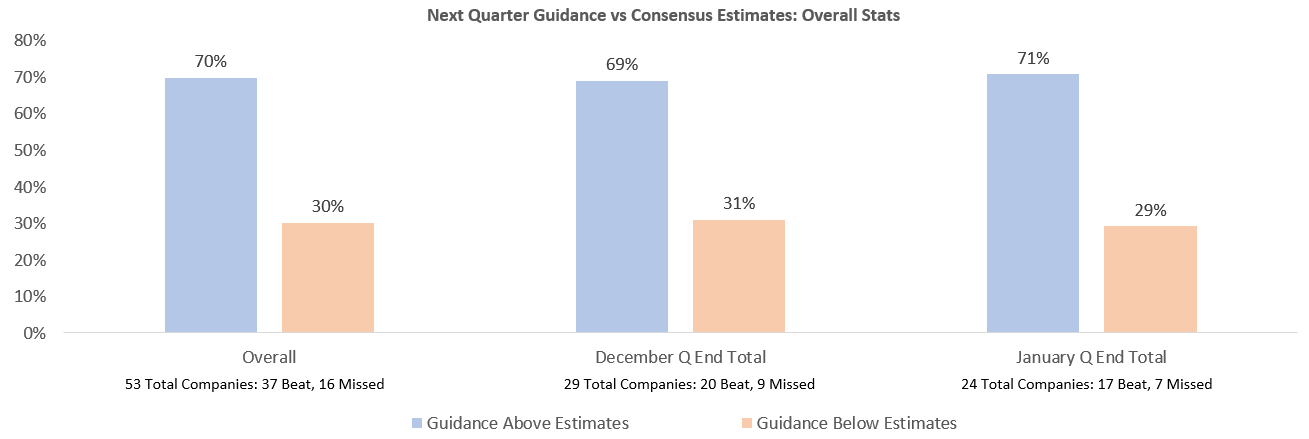

Next Quarter’s Guidance Relative to Consensus Estimates

Guiding above next quarter’s consensus revenue estimates is the second factor for a successful quarter. Generally, companies will give a guidance range (e.g., $95M -$100M), and the numbers I’m showing are the midpoint. Providing guidance that is greater than consensus estimates is a sign of improving business momentum, or confidence that the business will perform better than previously expected. The concept of guiding higher than expectations is considered a “raise.” When you hear the term “beat and raise” the beat refers to beating current quarter’s expectations (what we discussed in the previous section), and the raise is raising guidance for future quarters (generally it’s annual guidance, but for this analysis we’re just looking at the next quarter’s guidance).

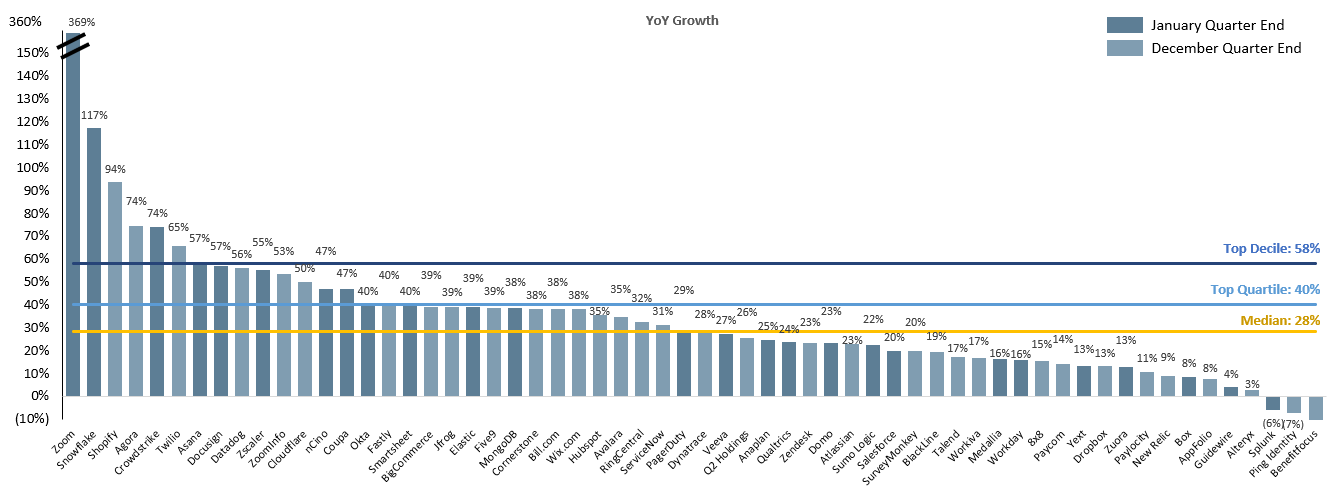

Growth

Demonstrating high growth is the third aspect of a successful quarter. This metric is more self-explanatory, so I won’t go into detail. The growth shown below is a year-over-year growth for reported quarters. The formula to calculate this is: (Q4 ’20 revenue) / (Q4 ’19 revenue) - 1.

As you can see from the data above, the median growth rate was 28%, a top quartile growth rate was anything >40%, and a top decile growth rate was anything >58%. It’s interesting to compare this to Q1, Q2 and Q3 (which you can see in the chart below).

FCF Margin

FCF is an important metric to evaluate in SaaS businesses. Profitability is often the big knock against them, however many generate more cash than you might imagine. I’m calculating FCF by taking the Operating Cash Flow and subtracting CapEx and Capitalized Software Costs. The big caveat in FCF – it adds back the non-cash expense of SBC. This is controversial, as it harms shareholder returns by increasing the number of shares outstanding over time (dilution).

As you can see, the median FCF margin was POSITIVE 10%! Top decile companies delivered 37% FCF margins.

Net Revenue Retention

High net revenue retention is the fourth aspect of a successful quarter, and one of my favorite metrics to evaluate in private SaaS companies. It is calculated by taking the annual recurring revenue of a cohort of customers from 1 year ago, and comparing it to the current annual recurring revenue of that same set of customers (even if you experienced churn). In simpler terms — if you had 10 customers 1 year ago that were paying you $1M in aggregate annual recurring revenue, and today they are paying you $1.1M, your net revenue retention would be 110%. The reason I love this metric is because it really demonstrates how much customers love your product. A high net revenue retention implies that your customers are expanding the usage of your product (adding more seats / users / volume - upsells) or buying other products that you offer (cross-sells), at a higher rate than they are reducing spend (churn).

Here’s why this metric is so significant: It shows how fast you can grow your business annually without adding any new customers. As a public company with significant scale, it’s hard to grow quickly if you have to rely solely on new customers for that growth. At $200M+ ARR, the amount of new-logo ARR you need to add to grow 30%+ is significant. On the other hand, if your net revenue retention is 120%, you only need to grow new logo revenue 10% to be a “high growth” business.

I’ve looked at thousands of private companies, and over time have come up with benchmarks for best-in-class, good, and subpar net revenue retention. Not surprisingly, these benchmarks match up relatively well with the numbers public companies reported. I generally classify anything >130% as best in class, 115% — 130% as good, and anything less than 115% as subpar. For businesses selling predominantly to SMB customers, these benchmarks are all slightly lower given the higher-churn nature of SMBs. I consider >120% best in class for companies selling to SMBs (like Bill.com). Here’s the data from Q4:

As you can see from the data above, the median net revenue retention rate was 115%, a top quartile net revenue retention rate was anything >124%, and a top decile net revenue retention rate was anything >132%. The one point to note: Not all companies report this number. It’s likely fair to assume that the majority of companies who don’t report this metric probably fall into the subpar category. Because of this, the median, top quartile, and top decile numbers mentioned above probably are better than reality.

Sales Efficiency: Gross Margin Adjusted CAC Payback

Demonstrating the ability to efficiently acquire customers is the fifth aspect of a successful quarter. The metric used to measure this is my second-favorite SaaS metric (behind net revenue retention) : Gross Margin Adjusted CAC Payback. It’s a mouthful, but this metric is so important because it demonstrates how sustainable a company’s growth is. In theory, any growth rate is possible with an unlimited budget to hire AEs. However, if these AEs aren’t hitting quota and the OTE (base + commission) you’re paying them doesn’t justify the revenue they bring in, your business will burn through money. This is unsustainable. Because of the recurring nature of SaaS revenue, you can afford to have paybacks longer than 1 year. In fact, this is quite normal.

All that said, Gross Margin Adjusted CAC Payback is relatively simple to calculate. You divide the previous quarter’s S&M expense (fully burdened CAC) by the net new ARR added in the current quarter (new logo ARR + Expansion - Churn - Contraction) multiplied by the gross margin. You then multiply this by 12 to get the number of months it takes to pay back CAC.

(Previous Q S&M) / (Net New ARR x Gross Margin) x 12

A simpler way to calculate net new ARR is by taking the current quarter’s ARR and subtracting the ending ARR from one quarter prior. Similar to net revenue retention, I’ve built up benchmarks to evaluate private companies’ performance. I generally classify any payback <12 months as best in class, 12–24 months as good, and anything >24 months as subpar. The public company data for payback doesn’t match up as nicely with my benchmarks for net revenue retention. The primary reason for this is that public companies can afford to have longer paybacks. At $200M+ ARR, businesses have built up a substantial base of recurring revenue streams that have already paid back their initial CAC. Their ongoing revenue can “fund” new logo acquisition and allow the business to operate profitably at paybacks much larger than what private companies (with smaller ARR bases) can afford.

Most public companies don’t disclose ARR (and when they do, it’s often not the same definition of ARR as we use for private companies). Because of this we have to use an implied ARR metric. To calculate implied ARR I take the subscription revenue in a quarter and multiply it by 4. So for public companies the formula to calculate gross margin adjusted payback is:

[(Previous Q S&M) / ((Current Q Subscription Rev x 4) -(Previous Q Subscription Rev x 4)) x Gross Margin] x 12

Here’s the payback data from Q4. Not every company reports subscription revenue, so they’ve been left out of the analysis.

As you can see from the data above, the median gross margin adjusted payback was 21 months, a top quartile gross margin adjusted payback was anything <14 months, and a top decile gross margin adjusted payback was anything <10 months.

Change in 2021 Consensus Revenue Estimates

Tying all of these metrics together is another one of my favorites: the change in revenue consensus estimates for the 2021 calendar year. Heading into Q4 earnings, analysts had expectations for how each business would perform in 2021. After earnings, that perception either changed positively or negatively. It’s important to look at the magnitude of that change to see which companies appear to be on better paths. Analysts take in quite a bit of information into their future predictions — exec commentary on earnings calls, current quarter results, macro tailwinds / headwinds, etc., and how they adjust their 2021 estimates says a lot about whether the outlook for any given business improved or declined.

As you can see, the outlook (according to analysts) for a number of these businesses really improved after this quarter.

Change in Share Price

At the end of the day what investors care about is what happened to the stock after earnings were reported. The stock reaction alone doesn’t represent the strength of a company’s quarter, so the below data has to be viewed in tandem with everything discussed above. Oftentimes the buy-side expects a company to perform well (or poorly), and the company’s stock going into earnings already has these expectations baked in. In these situations the stock’s earnings reaction could be flat. However, it’s still a fun data point to track.

What I’ve shown below is the market-adjusted stock price reaction. This means I’ve removed any impact of broader market shifts to isolate the company’s earnings impact on the stock. As an example, a day after PagerDuty reported earnings their stock was down 8%. However the market (using the Nasdaq as a proxy) was down 3% that same day. This implies that even without earnings PagerDuty would likely have been down 3%. To calculate the specific impact of earnings on the stock we need to strip out the broader market’s movement. To do this we simply subtract the market’s movement from the stock’s movement: (% Change in Stock) - (% Change in Nasdaq)

However, some of this data can be quite misleading. Many of the companies saw a big change in their stock prices leading up to earnings. Either a run up, or a draw down from market factors. In the below graph I’m looking at how the stock compared to 2 weeks prior to earnings. The data is below:

You can see that very few companies with January quarter ends had a positive reaction in stock price. Given the overall cloud market crashed quite a bit in that time frame it makes sense.

Wrapping Up

This quarter has been a wild ride for SaaS businesses. As a group they’ve performed quite well during these volatile times in the broader market, and in that sense the future looks bright.

Here’s a summary of the key stats for each category we talked about, and how the “Big Winners” performed. Zoom, Twilio and Shopify are my Elite Performers of Q4! . Hopefully this provides a blueprint for every entrepreneur out there reading this post on how to preform as an elite public company.

The Data

The data for this post was sourced from public company filings, Wall Street Research and Pitchbook. If you’d like to explore the raw data I’ve included it below. Looking forward to providing more earnings summaries for future quarters! If you have any feedback on this post, or would like me to add additional companies / analysis to future earnings summaries, please let me know!

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not constitute an offer to sell, or a recommendation to purchase, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security, nor a recommendation for any investment product or service. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, neither the author nor any of his employers or their affiliates have independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author and all employers and their affiliated persons assume no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

First class analysis Jamin. Thank you

Outstanding Jamin, thank you!