Clouded Judgement 1.19.24 - The Bar for Going Public

Every week I’ll provide updates on the latest trends in cloud software companies. Follow along to stay up to date!

The Bar For Going Public

There’s a lot of talk recently about “are IPO markets open” or “what scale do I need to get public.” If we look historically at the period from 2015-2020 (ignoring 2021 IPOs) the rough medians were ~$200m ARR (minimum was $100m ARR), 50% YoY growth, and >120% net retention. You can find more details in this post I wrote a few years ago. These figures are incredibly impressive! There are very few companies that ever get to $200m, let alone can sustain 50%+ growth at >$100m ARR scale. The bar for going public has always been incredibly high. And I do think there area couple reasons why this bar is starting to creep up.

When we think about public market investors, buying the stock of a venture backed company who recently went public means parting ways (ie selling) other stocks in their portfolio (need the cash to make a new purchase!). The is a very real opportunity cost. And the challenge today is there are some very impressive public businesses who make that opportunity cost question tricky. Looking at some of the tables I post below, there are companies like Crowdstrike, Snowflake, Datadog, Zsclaer, etc who are all growing >30% with FCF margins in the 25-30% range. And companies like Microsoft. Salesforce, Adobe, and other larger incumbents who have historically been compounding machines. If you’re a private company growing 30%, but burning a lot of money, you have to ask yourself why would a public market investor buy my stock when there are alternatives like the ones listed above? The answer is they may, but just at a different price / valuation.

The difficulty with new IPOs is they have qualities that companies with longer tenures in the public markets typically don’t have: They typically have more concentrated ownerships, they aren’t as liquid (lower daily trading volumes), they’re generally much bigger culprits of higher stock dilution, and the team simply hasn’t had time to build trust with public market investors. These are just a few of the challenges / hurdles venture backed companies face.

So what can startups do today who have aspirations to go public? It starts with understanding what type of profile is attractive to public market investors, and I hope the weekly data I share helps give folks an understanding for what these types of metrics are. One thing I do want to call out that I don’t see tracked enough is stock compensation. For many companies, this can be viewed as somewhat of a free expense. An option pool that is simply re-upped at each round. However, it’s not free, and public market investors will typically place a lot more scrutiny on this metric than private investors do. I think it’s good hygiene for every founder to have a sense for what their annual "stock burn” is. Look at it quarterly! In the same way companies look at an ARR waterfall, look at a share count waterfall. Start with your beginning shares in a quarter, add the newly granted options, new grants from refreshes, and subtract the canceled unvested options from employees who departed. And look at how that figure grows on a quarterly basis! You really don’t want to be >5% of annual stock dilution (~1.25% / quarter) when you go public. In the same way the “gold standard” today is 30% growth and 30% FCF margins, the gold standard for equity dilution is 30% growth with 1-2% annual dilution.

And many companies may say an IPO is not the ultimate liquidity path for our business. Or realize they just can’t hit the metrics required to be attractive to public market investors. These are some of the “hard truths” founders and their boards should have open and honest conversations about. And that’s totally fine! Only a small number of startups will ever reach it to the public markets. But I do think there’s value to coming to that conclusion sooner than later.

Top 10 EV / NTM Revenue Multiples

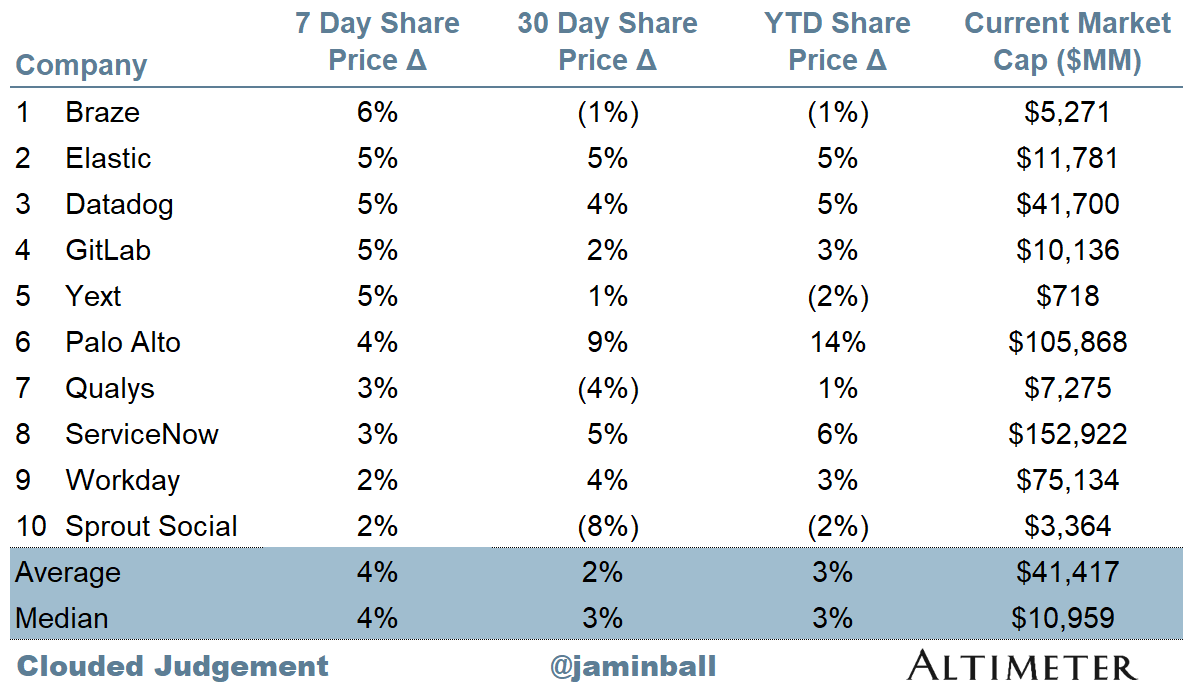

Top 10 Weekly Share Price Movement

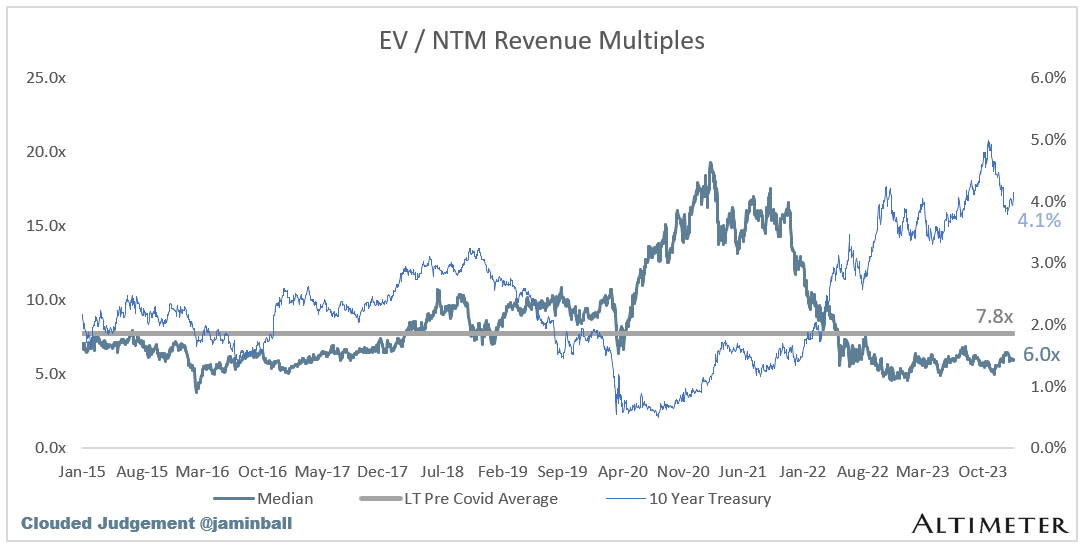

Update on Multiples

SaaS businesses are generally valued on a multiple of their revenue - in most cases the projected revenue for the next 12 months. Revenue multiples are a shorthand valuation framework. Given most software companies are not profitable, or not generating meaningful FCF, it’s the only metric to compare the entire industry against. Even a DCF is riddled with long term assumptions. The promise of SaaS is that growth in the early years leads to profits in the mature years. Multiples shown below are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value (market cap + debt - cash) / NTM revenue.

Overall Stats:

Overall Median: 6.0x

Top 5 Median: 16.8x

10Y: 4.1%

Bucketed by Growth. In the buckets below I consider high growth >30% projected NTM growth, mid growth 15%-30% and low growth <15%

High Growth Median: 15.0x

Mid Growth Median: 8.9x

Low Growth Median: 4.2x

EV / NTM Rev / NTM Growth

The below chart shows the EV / NTM revenue multiple divided by NTM consensus growth expectations. So a company trading at 20x NTM revenue that is projected to grow 100% would be trading at 0.2x. The goal of this graph is to show how relatively cheap / expensive each stock is relative to their growth expectations

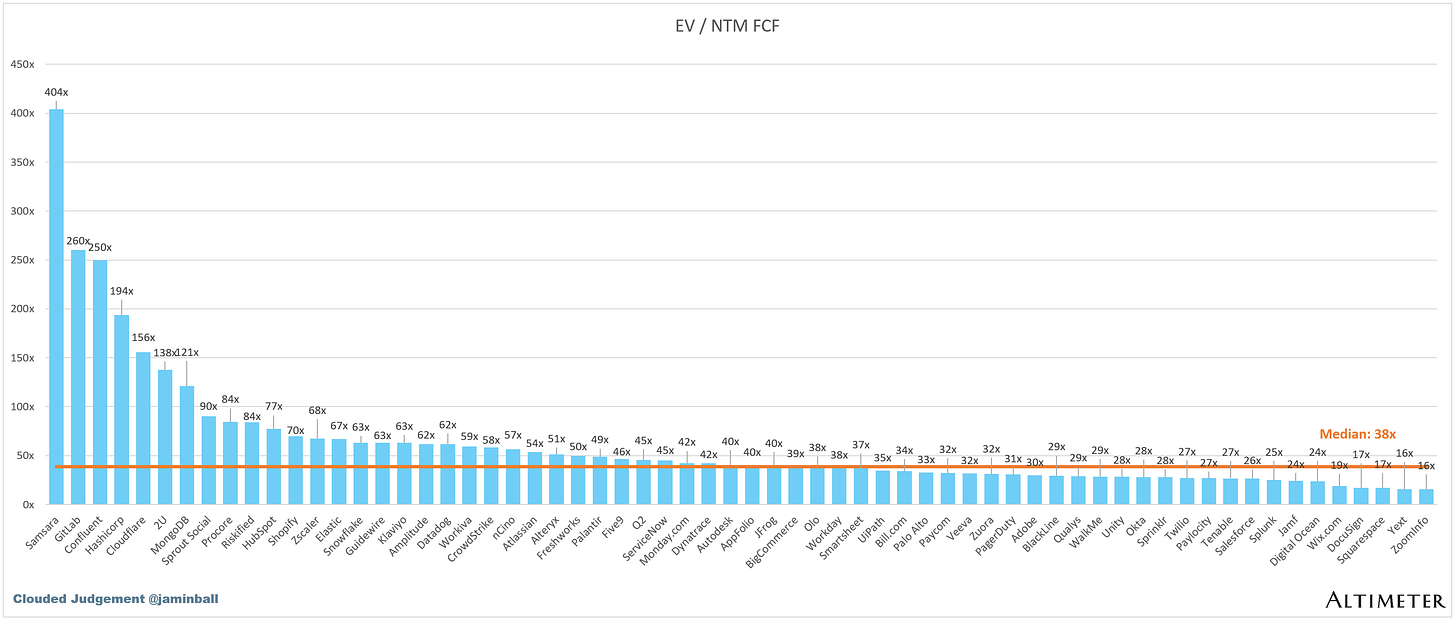

EV / NTM FCF

The line chart shows the median of all companies with a FCF multiple >0x and <100x. I created this subset to show companies where FCF is a relevant valuation metric.

Companies with negative NTM FCF are not listed on the chart

Scatter Plot of EV / NTM Rev Multiple vs NTM Rev Growth

How correlated is growth to valuation multiple?

Operating Metrics

Median NTM growth rate: 13%

Median LTM growth rate: 20%

Median Gross Margin: 75%

Median Operating Margin (13%)

Median FCF Margin: 8%

Median Net Retention: 112%

Median CAC Payback: 39 months

Median S&M % Revenue: 43%

Median R&D % Revenue: 26%

Median G&A % Revenue: 17%

Comps Output

Rule of 40 shows rev growth + FCF margin (both LTM and NTM for growth + margins). FCF calculated as Cash Flow from Operations - Capital Expenditures

GM Adjusted Payback is calculated as: (Previous Q S&M) / (Net New ARR in Q x Gross Margin) x 12 . It shows the number of months it takes for a SaaS business to payback their fully burdened CAC on a gross profit basis. Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, so I’m taking an implied ARR metric (quarterly subscription revenue x 4). Net new ARR is simply the ARR of the current quarter, minus the ARR of the previous quarter. Companies that do not disclose subscription rev have been left out of the analysis and are listed as NA.

Sources used in this post include Bloomberg, Pitchbook and company filings

The information presented in this newsletter is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect the view of any other person or entity, including Altimeter Capital Management, LP ("Altimeter"). The information provided is believed to be from reliable sources but no liability is accepted for any inaccuracies. This is for information purposes and should not be construed as an investment recommendation. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. Altimeter is an investment adviser registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not constitute an offer to sell, or a recommendation to purchase, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security, nor a recommendation for any investment product or service. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, neither the author nor any of his employers or their affiliates have independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author and all employers and their affiliated persons assume no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.