A few weeks ago I wrote an article summarizing Q1 earnings for public SaaS companies, highlighting what it takes to operate a successful public company from a metrics perspective. But for many startup entrepreneurs, a more helpful analysis would entail looking at what it took for each of these companies to become public in the first place. So in this article I’ll do just that, examining every SaaS IPO since the beginning of 2018, plus a few other influential IPOs before that period (36 in total), and analyzing how they all stacked up on a few key operating metrics at the time of their IPO. My hope is that every SaaS entrepreneur can use this data to set goals for themselves around what it takes to become a public SaaS company. There’s a lot to unpack here, so today, in part 1, I’ll go deep on benchmarking operating metrics. In part 2 I’ll analyze what a successful IPO process consists of — the 2-week investor roadshow leading up to the pricing of the IPO plus the first day of being publicly traded.

If you don’t have time to read the entirety of this article, here are the takeaways I hope everyone comes away with. To become a public company, every SaaS founder should aim for:

$200M ARR (minimum $100M)

90% of revenue derived from subscriptions

50%+ YoY ARR growth

$18M of net new ARR in the quarter you go public

72% gross margins

121% net dollar retention

25 months gross margin adjusted CAC payback

(31%) LTM operating margin

Are the SaaS IPO Markets Open?

Before we dive into the metrics and what it takes to go public, let’s talk a little about this concept of whether the markets are “open” for IPOs or not. I hear this question any time market volatility spikes and multiples compress — so I’ve obviously been hearing it a lot lately, too. Many people had said IPO markets were “closed” over the last 6 months (and felt justified in saying so) given there was a 6 month gap between Bill.com’s offering in December to ZoomInfo’s offering in June without any other SaaS IPOs (driven by Covid-19 volatility). But I have to say, I completely disagree with this premise. I don’t think the IPO markets are ever closed as long as large institutional investors and mutual funds have capital to deploy — and I don’t see that ability ever really going away. Instead, I’d assert that during these turbulent times the IPO markets are always open, but the filter through which companies are evaluated changes. As volatility goes up, mutual fund’s risk appetite goes down, and only the best businesses can create enough interest for a large equity offering. In the below sections I’ll call out every company that historically went public during one of these “closed windows” and contrast them to overall medians. I believe the data (with few exceptions) supports my claim, and you’ll see that the IPO markets are always open for exceptional businesses.

Before diving in, let’s level set on the periods of high volatility we’ll cover, and define the list of companies that went public to “re-open” the markets during these times. In the graphic below I’ve highlighted the windows I’ll discuss. I looked back 5 years to find all the points in time that might be considered a “SaaS crash"“: Toward the end of 2015, multiples dropped by 55%, and we saw a 6 month SaaS IPO hiatus before Twilio went public in June 2016. In the Fall of 2018, the threat of a trade war caused multiples to drop 31% and we again saw a 6 month hiatus before Zoom and PagerDuty went public in April 2019. Finally, earlier this year, Coronavirus fears sank multiples by 40%, and for the 3rd time we saw a 6- month SaaS IPO hiatus before ZoomInfo went public just a few weeks ago.

To summarize, the set of companies I’ll be highlighting in each section below that went public when the markets were “closed” are Twilio, Zoom, PagerDuty and ZoomInfo. You’ll see in the data that these companies on average performed much better than the overall basket, which supports my claim that the IPO markets are always open for the best companies.

Metrics Benchmarking

In the below sections I’ll walk through a number of key operating metrics and lay out how every SaaS business that went public in the last few years performed. There’s enough data points here that we can pull out trends and confidently state “what it takes to go public” with respect to each metric.

Top Line: Revenue, ARR and Growth

LTM Revenue

Total revenue may be the biggest gating factor to going public. Companies simply need a certain scale for public markets to be receptive. At the end of the day, SaaS businesses are valued off a multiple of their revenue (i.e., revenue determines their valuation), so this metric is king. I view it more as a binary metric: You are either big enough or you're not. Ultimately, looking at revenue scale in isolation doesn’t tell you much about a business. With that being said, here’s how each of those businesses fared when looking at their LTM (last twelve months) revenue at the time of their IPO:

As you can see, most businesses fell into the $150M - $250M range, and very few had <$100M. When we look at the 4 businesses that went public during a “closed window” there are no obvious trends that stand out in relation to market preferences. ZoomInfo and Zoom both were quite large, Twilio was right in the middle, and PagerDuty was on the smaller end. To me this further demonstrates the binary nature of revenue. Founders should aim for ~$200M of LTM before going public.

Implied ARR

The numbers are similar when looking at ARR (annual recurring revenue), which is a metric most founders at startups track more closely than overall revenue. With subscription models, ARR should be more of the north star metric. It’s easier to calculate ancillary metrics (churn, expansion, ACV trends, etc) when ARR is the guiding metric, and paints a more accurate point-in-time picture of the overall health of the business. However, despite my love for ARR, the public markets still use a multiple of revenue to imply valuations. Because of this, when companies feel like they are about a year or two away from IPO is when revenue should be tracked equally with ARR. Most public businesses do not disclose ARR, so in the graphic below I’ve shown implied ARR — most recent quarters subscription revenue x 4.

Similar to revenue, most businesses had anywhere between $150M - $250M ARR, and none had <$100M.

% revenue derived from subscriptions

It’s important to note that SaaS businesses generate different types of revenue — subscription, maintenance, license, professional services, etc. Generally subscription is the largest, and most valuable, piece. It often comes with higher margins as it’s pure software (no people costs to deploy it), and because of this, the markets typically value it higher with a higher multiple. The argument is every dollar of software revenue is “worth” more because it generates more gross profit.

The most obvious company to look at to see how the markets value lower gross margin businesses is Twilio. They are currently growing ~70%, with best-in-class net retention and payback unit economics. However, they have 55% gross margins. Twilio’s margins are not lower because of professional services. They are lower because they “rent” telecommunication infrastructure and “pass through” a percentage of their revenue to telco providers. Because of its lower GM, Twillio trades at ~17x forward revenue while its high-growth SaaS peers are trading at ~25x. The ~30% discount the market assigns to Twilio relative to its high-growth peers is because the market has concluded that every dollar of Twilio revenue is worth less than a dollar of revenue from someone like Datadog.

Now, circling back to professional services revenue. Generally professional services revenue, as shown by Twilio, is a lower gross margin revenue stream. Typically professional services implies there’s a larger human component to deploying your software. This could include sending individuals on-site to your customers office to help them deploy or implement the software. This human labor component comes with a cost. There’s a general consensus that professional services revenue is “bad” because it’s lower margin. I actually disagree with this sentiment. Professional services revenue can be bad if companies have to leverage them to onboard new customers. This could imply your customers either aren’t ready for your solution, or don’t understand it enough. In either case, your product probably doesn’t have true product-market-fit, and you’re using human resources to force a solution down your customers throats. This inherently won’t scale. On the other hand, if your solution is attacking a heavily legacy-solution-dominated market where you’re either moving them to a cloud solution, or changing the way they think about solving a problem, you may need this human labor to make your customers successful initially. They need this hand-holding to successfully go through “change management” to get up and running. Without it, your customers may never truly realize how to use your product correctly, might not understand the power it offers, or roll it out to enough users to make it sticky. This in turn could lead to higher levels of churn that should have been avoidable. Looking at it this way, you pay a small price up front, and in the long run reap the benefits of true software margins and the professional services go away (only used for implementation). As companies get big enough they can often leverage system integrators (SIs) or channel partners to implement these services. The one piece of advice I’d give to founders: If you’re worried your professional services revenue is too high, track professional services revenue as a percentage of new bookings every quarter. What you’d like to see is this steadily going down over time. And if you’re still worried, look at Workday. When it went public nearly 40% of its revenue came from services. Today that number is just under 15%, and its gross margins are 70%. They’ve also expanded their market cap nearly 9x from $5B to $45B. Workday is a perfect case study on how to effectively leverage professional services revenue early on to build a successful and thriving business.

In the chart below you can see the percentage of subscription revenue each company generated when compared to total revenue over the last 12 months.

Clearly you can see the market in turbulent times was more receptive to pure subscription models. This is not surprising given the predictability of subscription revenue.

Net New ARR

Peeling back ARR one layer further, we look at net new ARR added in the most recent quarter prior to IPO. Net new ARR is:

New logo ARR + expansion ARR - churned ARR - contracted ARR in a quarter.

Or, simply taking the ending ARR from one period and subtracting the ending ARR from 1 quarter prior. I place a lot of emphasis on this metric when evaluating private companies raising funding rounds. I don’t care about the absolute value of it, but rather the trajectory. I love to see the net new ARR added every quarter going up. It shows growth is accelerating, and the go-to-market team is successfully scaling. When looking at “what it takes to go public” we’ll just look at the absolute value to give founders a target. You can see the data below:

Net new ARR is a derivative of growth (or is growth a derivative of net new ARR? My calculus days are too far behind me…). As a founder I’d target ~$15M of net new ARR / quarter as the benchmark to make it public. With the exception of PagerDuty, we see the other 3 businesses to go public in a “closed window” were all in the top quartile. This is the first sign of the importance of growth.

YoY ARR growth

Turning to ARR growth — here’s how fast each company was growing ARR YoY at the time of their IPO. And as a quick refresher, every time is say YoY (year-over-year), I’m taking the most recent period’s ARR and dividing it by the ARR from exactly 1 year ago to show an annual growth rate.

Again with the exception of PagerDuty, all of the businesses to go public in a “closed window” were in the top quartile. As a founder I’d target 40-60% YoY growth to make it to the public markets. There is clearly a separate category of businesses growing 75%+, which I’d consider best-in-class.

Another interesting way to look at the data is to order the business by growth (like the above graphic), but instead shade each bar based on how the stock reacted 1 year after the IPO. In the below graphic I’ve shaded the bars red if the company's stock price increased by 100% or more 1 year after IPO. As you can see, there’s a big grouping of red toward the left of the graph suggesting high-growth businesses were more correlated with increased stock returns. Veeva was the only company well inside the top quartile of growth whose stock did not double 1 year after IPO.

Unit Economics - Net Revenue Retention / Payback / Rule of 40

Net Revenue Retention

As I’ve mentioned before, net revenue retention is one of my favorite SaaS metrics. It is calculated by taking the annual recurring revenue of a cohort of customers from 1 year ago, and comparing it to the current annual recurring revenue of that same set of customers (even if you experienced churn and that group of customers now only has 9, or anything <10). In simpler terms, if you had 10 customers 1 year ago that were paying you $1M in aggregate annual recurring revenue, and today they are paying you $1.1M in aggregate, your net revenue retention would be 110%. Here’s how they all stack up on this metric:

All businesses to go public during a “closed window” had top quartile net revenue retention. Yes, I realize ZoomInfo is below the 139% threshold, but for a business with a big component of revenue from SMBs, I consider 109% quite good.

Gross Margin Adjusted CAC Payback

This is my second-favorite SaaS metric. To calculate it you divide the previous quarter’s Sales & Marketing expense (fully burdened CAC) by the net new ARR added in the current quarter (new logo ARR + Expansion – Churn – Contraction) multiplied by the gross margin. You then multiply this by 12 to get the number of months it takes to pay back CAC.

(Previous quarter S&M) / (Net New ARR x Gross Margin) x 12

In the below chart I’m showing the average payback of the 4 quarters leading up to IPO (this removes the effect of an abnormally good or bad most recent quarter’s payback). This metric is a good way to evaluate how sustainable a company’s growth is. For private companies I like to see payback around 20 months or less, and anything <12 months is best in class. When payback creeps up too high, it suggests your burn rate is too high, and ultimately when you have to decrease burn, growth will follow suit. The companies that can sustain high growth rates are the most successful in the long run.

Here I think you can really see the emphasis the market places on “efficient” businesses when we’ve been in a so-called “closed window.” As evidenced by the data, ZoomInfo, Twilio and Zoom all had best in class payback periods, and Pagerduty was just outside the top quartile. In many ways a short payback period is a good proxy for how long it will take a business to become profitable. A low payback implies profitability will come sooner rather than later (and you can sustain high growth rates), and public investors clearly value this.

Rule of 40

The final unit economic metric to look at, the Rule of 40, is another profitability-focused metric. You calculate it by combining the growth rate and the operating margin (YoY growth + operating margin). Here I’m using GAAP operating margin (more on that later). The general idea is growth comes at a cost, and by adding operating margin (which is generally negative) to the high growth rates in SaaS we get a better understanding of what that cost is and how sustainable / profitable that growth is. Usually the profitability metric used here is FCF margin (which will be higher than GAAP operating margin), but not all companies disclose FCF (or they have slightly different ways of calculating it), so I’m using GAAP operating margin to compare each business on a level playing field.

Again, with the exception of PagerDuty, each businesses to go public in a “closed window” typically fell to the left of this chart well inside the top quartile.

ACVs

The final metric to benchmark is ACVs, or Average Contract Value. In other words, the average value of a 1 year subscription. I don’t think the size of ACVs are an indicator one way or another of a company's success. This is more of an FYI metric for founders who want to benchmark themselves (on other metrics) against companies with similar ACVs.

To calculate the implied ACVs for each company I take the most recent quarter’s subscription revenue before IPO, multiply it by 4 (to get implied ARR), then divide by the number of customers disclosed in the prospectus.

Margins / Expense Ratios

There’s less analysis to discuss when looking at margins / expense ratios (given they’re all fairly straightforward), but I wanted to present the data. Despite their straightforwardness, they’re still very important for entrepreneurs to track and benchmark themselves against. If your margins are materially lower than any of the medians presented below it’s important to understand why, and have a plan going forward for margin expansion.

Gross Margins

Not surprisingly, the markets had a preference for higher gross margins during “closed IPO windows.” While Twilio had lower gross margins, it had exceptional payback and net retention,which made their model quite attractive despite the low gross margins.

LTM GAAP Operating Margin

Unfortunately not many cloud businesses are profitable when they go public. However, the promise of SaaS recurring revenue is that over time (after the initial acquisition costs are paid back), it becomes extremely profitable. The length of payback period (a metric we discussed earlier) shows how long it takes each revenue stream to become profitable. Operating income is traditionally the most straightforward profitability metric, but EBITDA and FCF can also be used. In this analysis I’m using GAAP operating margin. Stock based compensation (SBC) which refers to the equity compensation companies provide employees (often higher in tech companies) is INCLUDED in GAAP operating expenses, along with other things, thus lowering margins. Most companies track non-GAAP operating margin (or free cash flow which is another Non-GAAP metric) closer as it strips out this non cash expense. Because SBC can vary wildly from company to company I’ve shown GAAP operating margin to create a more apples-to-apples comparison. The debate on whether GAAP or Non-GAAP operating margin should be the standard has been going on for a while - maybe I’ll dive into this issue in another post :)

LTM Sales and Marketing (S&M) Expense % Rev

Sales and Marketing costs are the expense line item that can balloon the quickest. Typically when S&M costs are “too high” the payback period starts to creep up. As long as your payback period is low it’s OK for the S&M expenses to be higher. Zoom is a perfect example of this. Their payback is best-in-class at 13 months, but on an absolute basis its S&M expenses as a percentage of revenue is middle of the pack. This is absolutely OK. Issues arise when both payback and S&M as % or revenue are both above the median. When this happens there are a number of issues that could be the root cause, including hiring unproductive AEs who can’t hit quota, churn issues, a market that’s not ready for your product, or many more.

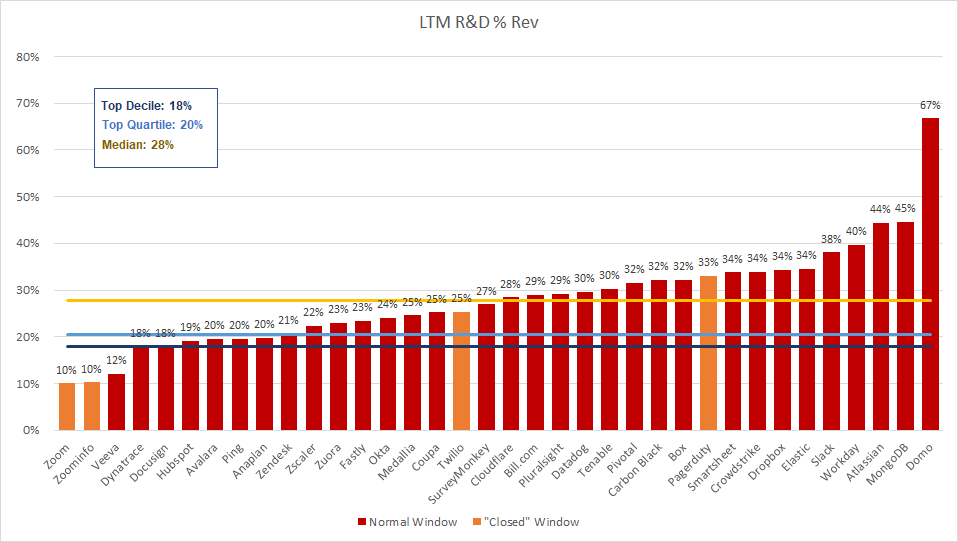

LTM Research and Development (R&D) Expense % Rev

Early on, I love to see companies operating expenses dominated by R&D. It shows the company is heavily investing into a product that is hard to replicate. Once businesses start to hit $5M - $10M in ARR is when the R&D starts to flip to S&M as the go-to-market functions kick in. Typically companies land at R&D costs taking up 25-30% of revenue. The interesting callout here is how little both Zoom and Zoominfo spend on R&D.

LTM General and Administrative (G&A) % Rev

G&A costs should stay relatively constant as a percentage of revenue. In my opinion anything >30% starts to be too high.

Wrapping Up

This has been a very data intensive post with a number of key points throughout, so I wanted to summarize everything below. As a general rule of thumb, and in order to have the most successful IPO, as a founder / CEO I would target the median metrics in each category as my IPO Goals. I’ve included my own take on the minimum (maximum for payback and expense ratios) thresholds for each category as well.

Next week I’ll publish part 2 that dives into the actual process of an IPO itself. Among other things, I’ll discuss how much money companies raise through IPOs, at what dilution, and go deep on the controversial topic of an “IPO pop” and how bankers price IPOs.

Thanks for reading!

Interesting breakdown of the journey to becoming a public company. What do you think is the most critical factor in this process? visit also https://www.thesaastalk.com/

Nice write up Jamin! I was wondering if there was a source from where I could arrive at the LTV or ACV of various publicly listed SaaS companies. I have been trying for sometime now but Gross Retention data seems hard to find.