Clouded Judgement: IPO Process Overview - Are IPO Markets Opening Soon?

A little over 3 years ago I wrote a post about the IPO process, outlining what happens at each step along the way. The post was a qualitative review of the IPO process, as well as a quantitative review benchmarking the key pieces of an IPO. The benchmarking was not a review of business metrics (I did some of that benchmarking in this post), but rather IPO metrics. Things like offering size, float, dilution, filing range multiple relative to comps, etc.

We now haven’t seen a software IPO in nearly 2 years (Samsara was the last one in December 2021). With the Nasdaq up almost 40% this year (!) it’s fair to assume we’re getting closer and closer to the IPO window opening again. Given that, I thought I’d update the post I referenced above from 3 years ago with the incremental IPOs we’ve seen since.

The main purpose of this blog is to be a resource for founders, entrepreneurs, executives and employees at startups and late stage private businesses. The public markets can often be quite confusing (and different) from private markets. Yet many individuals don’t really start paying attention to the public markets until they have to (their company get’s close to going public). The hope is this blog can give everyone a “drip-feed” of the IPO process and public markets so the transition is easier from private to public. And with the IPO markets almost certainly starting to “thaw,” we hopefully have a number of companies thinking about their IPO now!

In this analysis, I’ll be looking at IPO processes as it relates to standard IPOs. Direct listings are an entirely different animal. Before we dive in, here’s a simple graphic to illustrate the normal IPO process / timeline that I’ll go into detail on in this article:

Step 1: The “Bakeoff”

Many of you have probably heard of this term. Once a company has decided it wants to embark on the journey to become public, the first thing it must do is select a group of investment banks. Throughout the IPO process the banks play a key role in helping each company prepare to go public (drafting documents, building investor presentation, etc), and ultimately tap into their relationships with large institutional investors to help sell IPO shares. At the end of the day each company only goes public once, while investment banks have taken hundreds (if not thousands) of companies public and have a wealth of experience to tap into. During a bakeoff, each bank will pitch the company on why they should be the one selected to lead the offering. The company will then select their lead bank, who is known as the “Lead Left Underwriter,” as well as the other banks who will help out throughout the process (known as joint book-running managers and co-managers). The purpose of the joint bookrunners is mainly twofold. First, they ultimately help with the placement (selling) of the IPO shares. Second, they all end up publishing quarterly research reports which prove quite valuable to prospective investors. These reports are “sell side reports” (you’ve probably heard this term before). These reports in aggregate form the quarterly consensus metrics I talk about around quarterly earnings (consensus revenue for Q2 ‘23 for any software company is the median Q2 ‘23 revenue estimate from the aggregate set of sell side reports). If you look at the front page of any IPO Prospectus (the S-1 document), you’ll see a list of investment banks at the bottom of the first page. The upper-left name is the lead left underwriter, followed by the other banks involved. The bakeoff is done privately, and it is not made public that a company has gone through this process (though sometimes that info leaks!).

Step 2: IPO Prep - From Bakeoff to Public Filing

Once a company has selected a bank, there are a number of processes it must go through before going public. One of the more time-intensive processes is drafting the actual S-1 document itself. This is generally hundreds of pages and includes all the information about the company a prospective investor would need to know to help inform their investment decision. It includes a business overview, detailed historical financials, risks to the business, market sizing / data, cap table information, summary of past financing, and quite a bit more. The document is put through heavy legal scrutiny (trust me on this, every single number presented is meticulously fact checked with supporting backup by lawyers) and takes quite a bit of time to get right. Every entrepreneur should plan for at least 4-6 months (but probably more like 6-8 months) for this process. At some point in the drafting phase a company may decide to “confidentially” file the document with the SEC (although more often than not this ends up getting leaked to the press!). They do this to privately solicit feedback / comments from the SEC. Like the lawyers, the SEC will go over the document in detail (and also fact check every number), and let the company know what edits they need to make before the document can be made public.

In addition to drafting the S-1 document, the company will prepare audited historical financials, detailed forward model projections (income statement, balance sheet and cash flow statement), and a company presentation that will be used pitch large institutional investors on their roadshow (more on that later). This all leads up to their public filing.

Step 3: Public Filing

Up to this point, everything the company has done is in preparation to go public at some point in time. There really is no deadline from the time a company conducts its bakeoff to the time it will publicly file the S-1 document. However, once the S-1 document has been filed with the SEC publicly it typically means the company is aiming to go public in the next ~3 weeks (there is a 2 week minimum time-frame before the roadshow can start). Therefore the timing of this public filing is quite important (you obviously want to go public at a time of relatively low market volatility).

The interesting aspect of the first public filing is that the S-1 document is often times not “complete.” Generally the deal-specific terms (how many shares are being issued, primary / secondary split, proposed dollars raised and price range, etc) are left out. When a company first files their S-1 the headlines in the press will read something like “Company X looks to raise up to $[Y]m dollars in proposed public offering.” Generally the dollar value is a placeholder, and often represents a minimum amount. For example, in ZoomInfo’s first S-1 filing, the proposed maximum offering amount was $500M, and they ended up raising $935M. You really can’t read much into the “initial proposed maximum” from the first S-1.

Over the next ~3 weeks the company will go over final edits with the SEC and fill in the details to complete their S-1. These are often filed as S-1 “Amendments.” The biggest changes here are a pricing range included in the S-1. This leads us to the launch of the IPO.

Step 4: Roadshow Launch + Initial Price Range

Once a company is definitively ready to “press go” on their IPO they file another S-1 Amendment that includes a proposed price range they wish to offer their shares at. This is typically done on a Monday, and the company will then spend the next 2 weeks flying around the country (and sometimes world) meeting and pitching prospective heavy-hitter investors. These investors include large mutual funds and hedge funds (who I’ll refer to as institutional investors), who are buying as much as 10-15% of the total offered shares from the IPO.

At this point we have a completed S-1, and there are a couple key items to unpack.

Type of Shares Offered

In an IPO, each company has 2 different types of shares they can offer. They can decide to offer shares themselves (primary) which simply means they are issuing new shares and selling them to raise money for the company. They can also decide to offer existing shares (secondary) in which case the shares being offered are being sold by existing shareholders. In these situations the individual shareholders who are selling receive the proceeds and the company receives nothing. Of course the company can also decide to offer a combination of both primary and secondary. Of the 45 SaaS IPOs analyzed in this piece 35 (78%) offered only primary, and 10 (22%) offered a combo of primary and secondary. If you open up a S-1 document and search for the term “The Offering” you can find the section that lays out these details. The shares labeled as “Offered By Us” are primary, and the shares labeled as “Offered By The Selling Stockholders” are secondary.

Setting the Initial Price Range

Setting the initial price range is a science and an art. First, let’s level set on what this pricing range means. In an IPO, companies sell shares (either primary or secondary like we described above) to a set of institutional investors. The price range (generally a $2 - $5 range) the company provides is meant to guide these institutional investors toward a price in which to place their limit orders should they choose to invest. Typically at the start of an IPO process the initial price range is set artificially low in order to build demand — I’ve gathered data to demonstrate this.

If we go back and look at the set of 45 SaaS IPOs (all SaaS IPOs since the beginning of 2018 plus a few more before that) we can clearly see that the implied forward revenue multiple of the midpoint of the range is well below the set of comparable SaaS businesses with similar growth rates at the time. To oversimplify this, here’s how we get from a share price to an implied forward revenue multiple.

You first take the share price (midpoint of the range) and multiply by the number of shares outstanding after the offering (I’ve also factored in the effect of options and RSUs, but I won’t go into that detail). This gives us an implied market cap.

We then convert this number to Enterprise Value by adding the total debt and subtracting the total cash balance (inclusive of any net IPO proceeds).

Finally, we divide this enterprise value by the forward (next twelve months) consensus revenue estimates to give us an implied forward revenue multiple.

It may seem complicated, but it’s actually rather straightforward. When the bankers and company are originally going through the exercise of setting the initial price range they’ll look at the multiples of a comparable set of SaaS businesses, and generally make the midpoint of the range a slight discount to the median multiple of this comparable set (again, this is done to drum up demand).

In the below graph you can see the implied multiple discount of the midpoint of the range from every SaaS IPO relative to the existing set of public SaaS businesses with similar growth rates:

As you can see, the midpoint of the initial range for most IPOs came in in-line with or at a discount to current trading multiples. The one thing I will note is this is a drastic oversimplification of how pricing ranges are set. The set of comparable companies is never limited to simply companies with similar growth rates, but for the purpose of this analysis that’s what I’m looking at (it’s definitely directionally accurate). I’ve bucketed each IPO into high, medium and low growth rate buckets (like I do in my weekly posts). High growth are companies projected to grow revenue >30% over the next year, medium growth is 15-30%, and low growth is <15%. I’ve then compared each companies implied multiple to the median multiple at the time of the same growth bucket. ie if a company is projected to grow 40%, I’ll compare their multiple at the midpoint of the filing range to the basked of public companies at the time in the high growth bucket (those projected to grow >30%).

Where the initial pricing range gets set in relation to these comparable buckets is part of the art! And it goes well beyond simply looking at growth rates. Business model, margin structure, unit economics, etc all factor into which multiple the company “deserves.” As you can imagine, it will be up to the company and bankers to convince investors that their comp set is the right one.

One other data point to show how the initial IPO range is typically set artificially low: The below graph shows the change in price from the ultimate IPO price (will talk about IPO pricing later!) to the midpoint of the initial range. As you can see, there were no IPOs of this set that priced below the midpoint of the initial range. As a reminder, this list is not a comprehensive set of SaaS IPOs. It represents every SaaS IPO from the beginning of 2018, plus a couple before then.

Roadshow / Revised Pricing Range

Once the initial IPO range has been set, the company, along with its bankers, hits the road for two straight weeks of investor meetings — this is called the Roadshow. These meetings are not too dissimilar from Series A / B / C meetings. The company pitches each investor on the business, its outlook, and why they should invest! It’s also a time for the company to get to know each firm. At the end of the day they’ll have the final say on who they give allocations to, and they want long-term shareholders. These meetings are a mixture of 1:1 meetings with large firms, large “group lunches” where a number (sometimes hundreds) of firms gather together for a lunch to hear the company pitch, and virtual / phone meetings. After each pitch the firms decide if they want to place a bid, or better known as an order. I’ll also note that orders are not restricted to firms who had a meeting; any institutional investor can place an order. These orders generally have two components to them: the maximum number of shares that firm would like to buy, and a limit price (which sometimes has “no limit”). As an example — if we look at ZoomInfo (which had an initial range of $16 - $18 and was selling a total of 44.5M shares), a fund like Fidelity might say “we’d like to place an order for 4.45M shares with a limit price of $19.” If that fund really wants to get an allocation (more on allocations later) they’ll make the limit price high. Over the course of the roadshow the bankers will keep track of every order, and the corresponding limit price. If the cumulative number of shares from the orders is greater than the total number of shares being offered by the company we say the IPO is “oversubscribed.” If an IPO isn’t oversubscribed it’s really really bad :) Back to ZoomInfo as an example - if the sum of all the shares from the individual orders was 89M we’d say the IPO was “2x oversubscribed.”

It’s not uncommon for IPOs to be 10x+ oversubscribed. The magnitude of the over-subscription is quite important. If the demand (the over subscription) gets high enough the company might decide to raise the price range. This is an art as well, as you have to factor in the prices of the orders. If the IPO was 10x oversubscribed, but the limit orders all came in below the guided IPO range you wouldn’t raise the price range. This is where the company leans on the bankers to provide guidance on whether to raise the range. Looking at the data, 31 of the 45 (69%) of the SaaS IPOs ended up raising the expected pricing range prior to pricing their IPO. You can see the date below:

Of the companies who raised their pricing range, the median raise was 16%

Step 5: IPO Pricing / Allocations

After the roadshow is complete (this is typically a Wednesday evening, 11 days after the roadshow launched the previous Monday), the company, bankers and board members will get together in a room and decide on the ultimate price for the IPO, and which investors they want to give allocations to (who they let buy). This is an incredibly nuanced process with many variables to consider. I’ll try and level-set on the important variables / terms, and then get into the actual mechanism for which the price gets set.

The Order Book

This is the master list of every firms order (# shares + limit price). It is often quite long.

Allocations: Selecting a Strong Investor Base

The term allocation refers to the exercise where the company goes through the order book and decides how many shares (if any) they want to award to each firm that put in an order. They can allocate each firm their full ask, a partial amount, or nothing. While going through allocations the key thing the company keeps in mind is their overall investor mix, and optimizing for a strong base of long term holders, with enough short term sellers to pump some supply into the market.

Different investment firms have different reputations (or different investment mandates, e.g. Mutual Fund vs Hedge Fund). Some are known as long-term holders, and others are known for trying to sell right away and flip a quick profit. It’s actually important that a company selects the right combination of both. They don’t want only long-term holders (as this would significantly restrict the number of tradable shares creating volatility in either direction), and they also don’t only want “quick flip” investors. If every investor sold right away. it would create significant downward pressure on the stock, and potentially start a dangerous downward spiral.

IPO Size

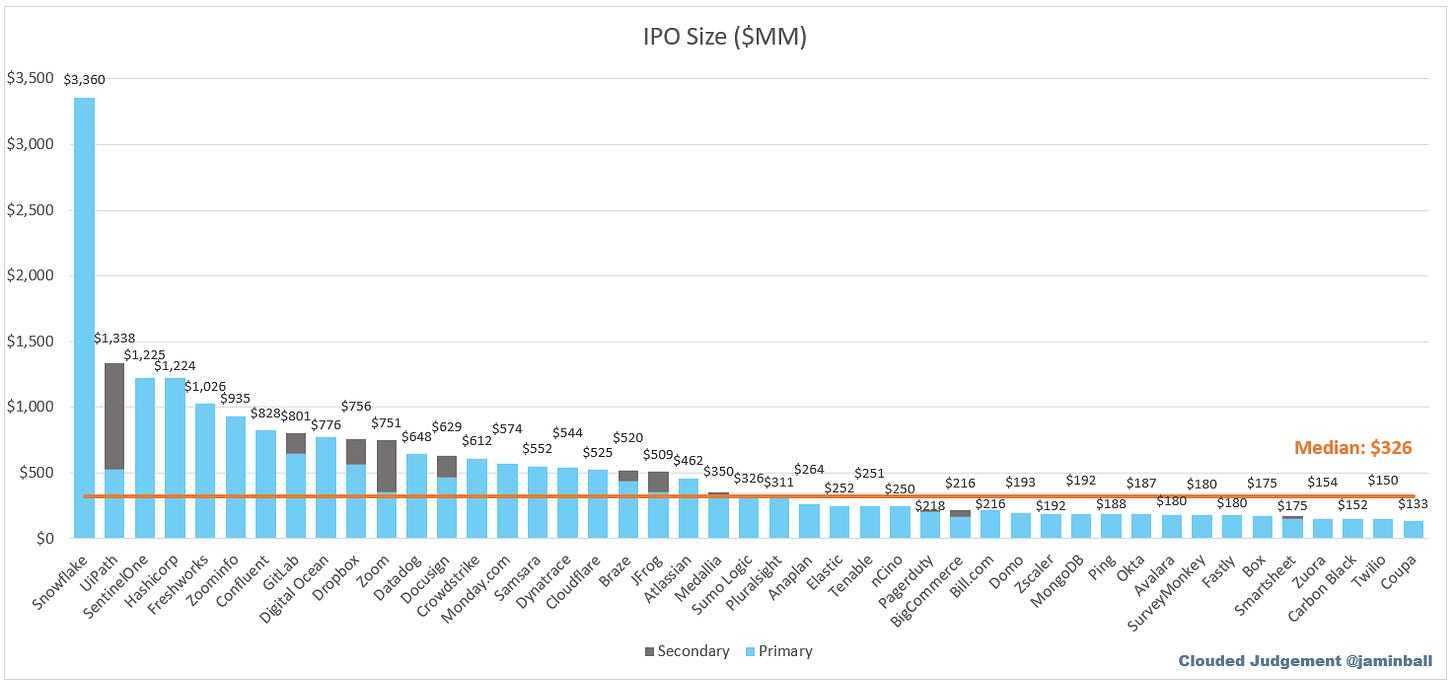

The IPO size is typically the number you see in press headlines — i.e., “ZoomInfo raises $935M in IPO.” This DOES NOT refer to market cap or any sort of valuation. It’s literally the size of the IPO, and simply refers to the IPO price x number of shares offered. The total dollar value represents to total value of shares placed with institutional investors. You can see a graph below of the IPO sizes for all SaaS IPOs analyzed here, with a split of primary / secondary

Float / Lockup

The float refers to the shares that can be traded on the open market right after the IPO (generally expressed as a percentage of the total outstanding shares), and the lockup refers to the existing shares that cannot be traded right after the IPO. If all pre-existing shareholders are “locked up,” it means that the only shares that are tradable on the open market day 1 of the IPO are the shares offered in the IPO (both primary and secondary). The float is generally expressed as a percentage: tradable shares not covered by lockup / total shares.

Typically all existing shareholders are not able to sell their shares on the open market for a period of 180 days (6 months), and this time period is known as the “lock up.” The purpose of the lockup is to twofold.

First, it’s meant to limit existing investors (often early investors whose entry valuation is significantly lower than the IPO valuation and may want to take a profit) all from selling their shares at once and flooding the market with supply. This would create significant pricing pressure on the stock (and drive it down). So the lockup basically allows the stock to “season” and reach more of a stable, equilibrium price.

The second purpose of the lockup is a regulatory one, meant to protect investors who are buying stock early on. The scenario the lockup is meant to protect is one where a company decides to go public while they’re doing well but on the brink of collapsing (or, less drastically, a company going public when they’re overvalued). Maybe internally they know their revenues are going to decline, or the company culture is in turmoil, etc. There are a whole host of reasons that the executives might be aware of (but no one else) that would incentive them to “get public before it’s too late!” A 6 month lockup allows the business to season before the execs and early investors are able to sell their shares. While the lockup has a definitive purpose, it also creates some issues, particularly as it relates to the float.

You can see the float of every SaaS IPO analyzed in this article below:

As you can see, the float is quite low as a percentage of overall shares outstanding. This will be important to remember when we discuss the IPO pop later on. One important point to make: The float only includes the shares bought by the institutional investors the day before at the IPO price (the IPO shares). However, not all of these shares will be traded on day 1. Many of the investors who bought IPO shares will be “long-term” holders, and their shares will never be added to the supply of tradable shares (because they don’t sell them on day 1). Because of this, the supply of tradable shares is often much smaller than the float. The effect is a limited number of shares in circulation, which commonly leads to big price swings early on. The float is an important variable to keep in mind when I discuss the “IPO pop” later on.

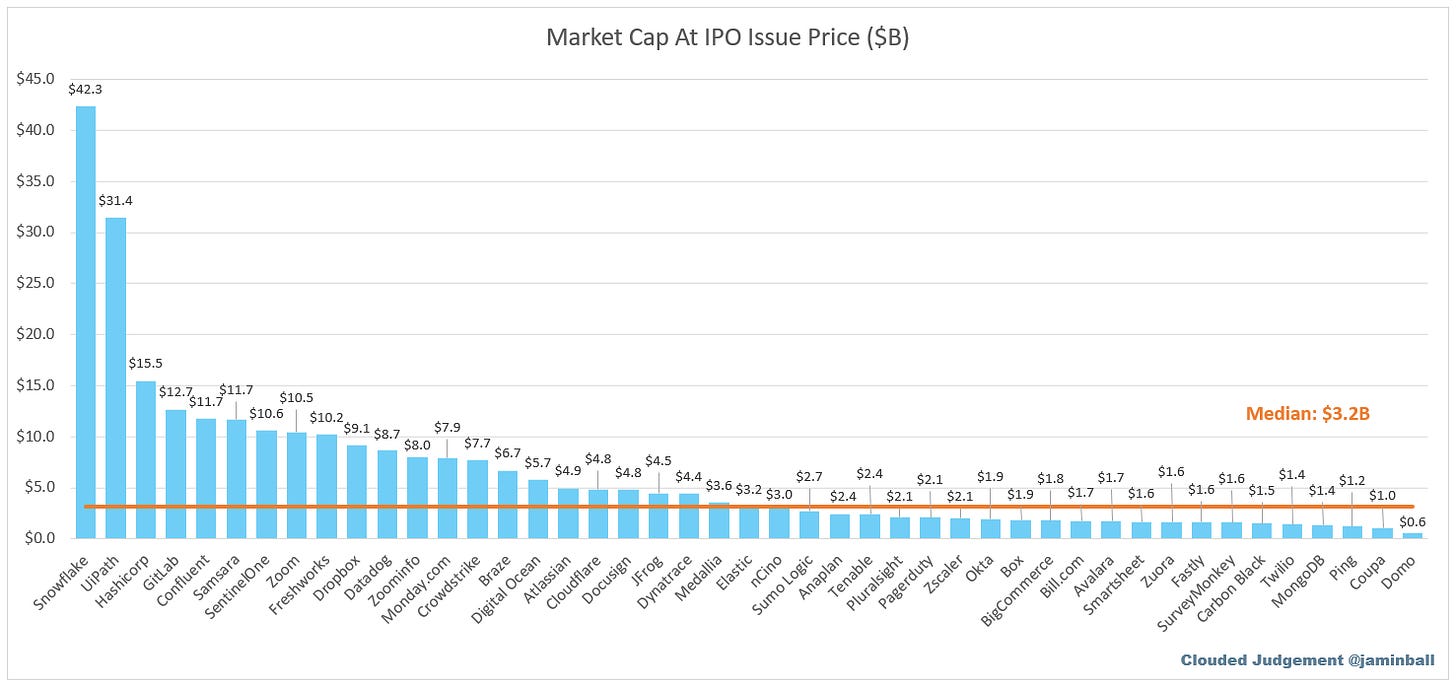

Market Cap at IPO

This is quite intuitive, and simply lays out the market cap of each company at its IPO price. The market cap is generally used interchangeably with a companies “valuation.” It’s calculated by taking the total number of shares x IPO price

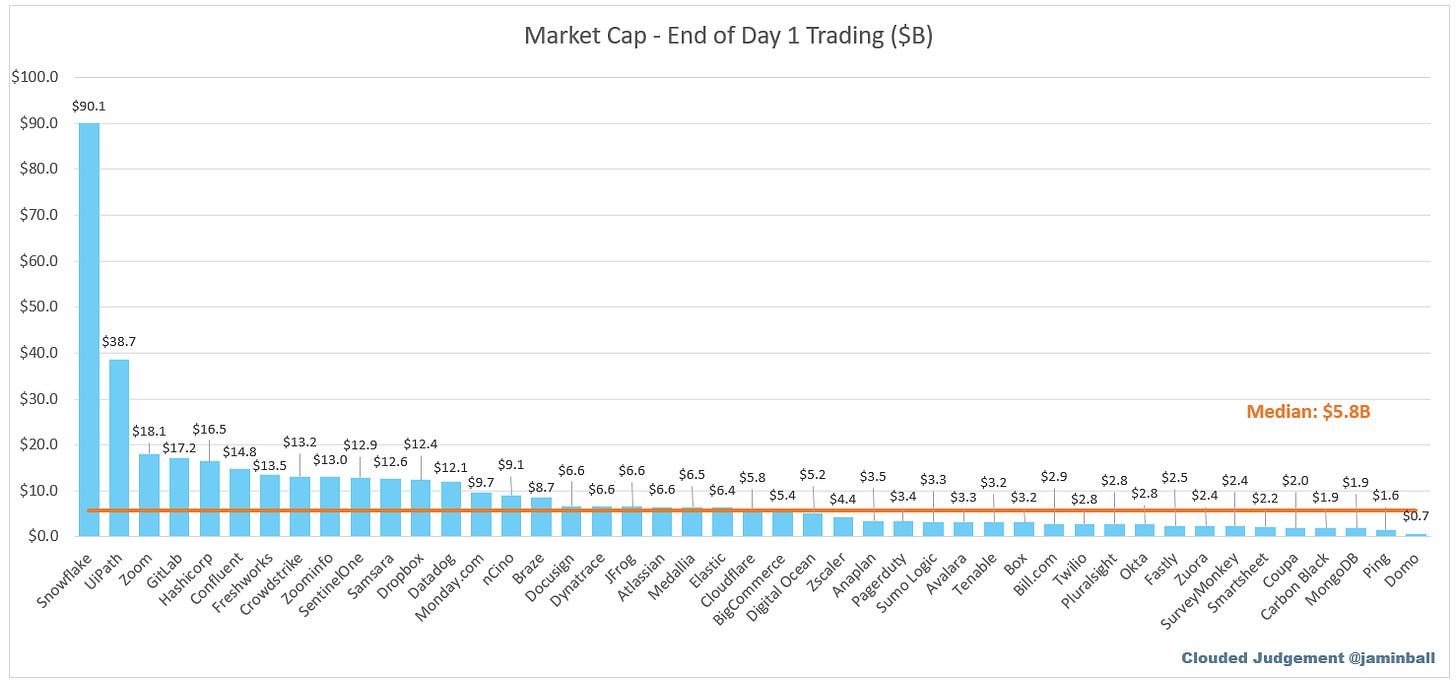

And the below graph shows the market cap of each company after day 1 of trading

IPO Dilution

Dilution refers to how much less of a company each existing shareholder will own after the new shares are issued (if total shares go up but your shares stay the same you own less). Many times people forget that the company does in fact take on dilution when raising IPO proceeds through primary / new share offerings! Below you can see a graph that lays out the exact amount of IPO dilution of each IPO. This does factor in the IPO price, and is only affected by primary shares offered.

Setting the IPO Price

Now that we’ve defined the key variables, we can get back to the key question of how the IPO price gets set. In any IPO, the company has 2 main goals (among others): 1) maximize the price (this maximizes their dollars raised at the lowest dilution) while 2) creating the “strongest” base of investors (what we described above in Allocations). The bankers typically have one goal, to set the company’s stock up for sustained success. A side goal for the banks may be to make the mutual funds / hedge funds happy, but I’ll leave that topic for another time :) How the bank would think of a “successful IPO” would be a modest ~25% “pop” of the stock the next day when it begins trading, while limiting the number of firms who dump their shares right away. The tricky aspect for all parties is thinking about maximizing the IPO price while also maximizing the strength of the investors. Typically the “best” institutional investors know the power they hold, and come in with low limit orders. I’ve personally been in situations where there was plenty of demand to price an IPO well north of the high end of the pricing range, but the few large / important mutual funds all had orders with limit prices somewhere within the range (and held steady). The company had 3 options in this scenario: 1) Ignore these “anchor” funds entirely and set the price higher with a base of more “risky” funds; 2) Set the price higher and go back to the anchor funds to see if they’ll come up (they generally don’t); 3) Set the price lower and include the anchor funds. For the situation I’m recalling, we ended up at option 3 (the lower price). Clearly, these large funds hold quite a bit of power, and this power is one of the huge inefficiencies I personally see in the current IPO process. So ultimately the act of setting the IPO price is an art that requires everyone to go through the Order Book and determine the maximum price that allows them to sell all of the shares they want to with the strongest base of investors. There is no formula / algorithm for this, it’s all done via conversations with the bankers and board heavily weighing in.

Earlier I talked about the implied revenue multiple at the midpoint of the initial filing range. The below chart shows the NTM revenue multiple at the IPO price of each IPO analyzed here. I’ve segmented them by the year they went public to show how things changed in the more recent years.

Step 6: Day 1 of Trading

Everything I’ve discussed so far leads up to the big moment of every IPO — ringing the opening bell of the NYSE / NASDAQ! These are the two main exchanges a company can choose to list their shares on. Similar to the investment bank bakeoff we discussed earlier, each exchange will pitch the company on why they should list their shares on their exchange. Each will give a “pitch” that includes listing fees, minimum number of shares that must be issued, and other services they offer. Shares will typically start trading Thursday morning (the morning after the IPO price was set and shares were sold to the large institutional investors). One interesting aspect is that the shares of a newly public company do not start trading at the opening bell at 9:30am ET. Instead, a market has to be created first. Retail investors (like you and me), as well as institutional investors who missed out on an allocation (or those who got one and want to increase their position) can all put in “buy” orders. Similarly, investors who did receive an allocation can put in “sell” orders. All of these buy / sell orders can be limit orders, or no limit orders. It is then up to the “market maker” to put together the order book of all of these orders and ultimately come up with an “open price” that effectively balances the buy / sell orders. This process has to happen because there was no historical market for the stock. Once this open price has been established, then the shares start trading! This is where you’ll see headlines like “ZoomInfo Rockets Over 80% in First IPO of Covid Era.” And now we get to the controversial topic of the IPO pop…

IPO Pop

The IPO pop is typically the percent change in share price from where it ends trading day 1 to where it was sold to the large institutional investors the day before. Before diving into the analysis, I’ll present the data for all SaaS IPO pops below. It’s interesting to note that only one of the IPOs lost value on day 1 (this is called “breaking issue price”).

If your immediate reaction is “Wow! Those IPOs must have been mispriced! Those companies left so much money on the table!” you’re not alone. The idea of money left on the table refers to the potential incremental dollars raised at higher prices. Agora, for example, priced its IPO at $20 / share and raised $350M in its IPO. The company then watched its share price jump 153% to $50.50 / share the next day. Since it had already sold, the business didn’t benefit from this massive pop. But theoretically shouldn’t they have been able to price their IPO closer to $50 (where it ended day 1) and raise more money?? While the answer clearly seems like a resounding “Yes!” there are nuances to unpack here and the answer is probably more “no” then “yes”. First, a day 1 pop is generally a bit artificial given the low float and supply of tradable shares we discussed above. This matters because an inflow of demand from retail investors, quant hedge funds, etc., meets a very low level of supply (float). These basic supply / demand economics drive the share price up (or could similarly drive it down in a different scenario). And remember, the actual shares in circulation are often lower than the float as many IPO investors hold onto their shares. If you look at the volume of shares traded on Day 1 this number is often greater than the total number of IPO shares meaning a single share is exchanging hands multiple times a day. Ultimately this means many flash trades can have big impacts on the stock price (driving it up). Also, for an IPO, (like a large block trade) to be able to sell that many shares at once, it will always come at a discount to what a “market price” would have been. To put in these kinds of large orders, institutional investors need some incentive (a certain profit). Otherwise they’d be better off just buying shares on the open market. In summary, often times the low float leads to artificially large “pops.”

Thus the banks, who are a core constituent in the pricing of IPOs, have to strike a delicate balance. The one thing that can absolutely not happen is for the stock to “break issue price” — when the stock trades below the price at which it was sold to institutional investors — on day 1, or any day during the lockup period. As we discussed earlier, this can create a dangerous domino effect of selling (with a limited supply of shares) plunging the stock downward. The Greenshoe is a complicated instrument that the banks can use to buy additional shares and support the stock if faces pricing pressure and falls, but this is too complicated of a topic to get into today. Because of this, the banks tend to be cautious on how they price. The “ideal price” that results in a modest pop the next day may not be possible. And this is a core point I’ll make when discussing why I believe the current IPO process isn’t ideal - an ideal price may not be possible.

As a hypothetical, let’s say Agora priced its IPO at $40, instead of $20 (and the point of this hypothetical is that the stock ended at $50 on day 1). This new price may have greatly softened initial demand from the market. In this scenario, there’s actually a chance that since the demand was lower, the price may have actually opened up BELOW the $40, causing the IPO investors to sell their shares to protect against the potential domino selling. This selling would then put downward pressure on the stock. In this situation the exact same company would end up with a different share price at the end of day 1 trading. The point I’m trying to make is that in the current IPO process it is VERY HARD to perfectly price.

And this brings me to my final point on pricing: The current IPO process isn’t ideal. Companies are shopped at a discount to large funds, and coming up with the IPO price has too many flaws. In today’s day and age it should not be this hard to come up with an efficient price (but it is with the current pricing mechanisms). Especially when large institutional investors have massive, sometimes 100%+ profits after just 1 day. The process clearly favors the large institutional investors at the expense of companies and retail investors.

The counterpoint here is that the price to look at to truly evaluate whether an IPO price was “right” is the price at which each stock trades once the lockup ends, and the full supply of shares are tradable on the open market (but this is also not totally apples-to-apples because over those 6 months the business has grown as well and is “worth more”). Below you can see the data for the change in share price from the IPO price, to share price right after the lockup expired. Most commonly a lock up is 6 months. However, there are instances where it may be shorter or longer than this. I didn’t actually comb through each filing to get the exact lock-up date for each IPO, but rather looked at the price 6 months out for each.

As you can see, the share prices are still (on average) drastically above the IPO price. This data is a little skewed given the nigh number of IPOs from 2021 (where the 6 month lock-up expiration date fell within the covid bubble where everything was trading up).

It’s really hard to have “perfect pricing.” An average pop of 48% (median of 34%) from IPO price to the expiration of the lockup might not feel “right.”

Unfortunately an adequate alternative to our current IPO process does not exist. A direct listing is a major step in the right direction; however, it has some major downsides. Namely, companies can’t raise primary capital, and the huge supply of shares that hit the market can put pressure on the share price (just look at Slack and Uber’s share price 3-5 months after their IPO to see examples of this). There have been developments in late 2022 that looks to change this. Seems like companies will be able to raise primary capital in direct listings coming up. I may dive into the nuances of direct listings in a future post.

I’d like to have all the answers, but I don’t. Some key drivers of inefficiency in my mind are the low float and power of the institutional investors. I’ve seen suggestions around “rolling out” IPO shares to the open market on a daily / weekly cadence and selling smaller block trades along the way at slight discount to market prices. Or finding some way to “drip feed” out locked up shares more gradually to add supply to the market. I hope this post fosters a healthy discussion around how the IPO process can be improved. My goal in writing this article is to make the IPO process more transparent so everyone has a better understanding of why exactly companies may “pop” on day 1, while appreciating how nuanced and difficult the pricing of IPOs can be (given the current limitations of the IPO process). Hopefully in the future we’ll see companies better able to maximize their dollars raised through Initial Public Offerings!

Awesome write up! This summary aligns with what I've seen (from studies while at business school, as an operator in a post-IPO SaaS company, and as a retail investor), and gives solid data and discussion to validate some hunches and offer some new insights. Thanks so much Jamin!